Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) Mathematics at the Vietnamese High School

GS.TS. Thái Văn Thành, TS. Phan Hùng Thư (và cộng sự)

Abstract

The implementation of content and language integrated learning (CLIL) has been enforced by many education systems across the world as a means of improving their foreign language education or strengthening multilingualism in their society. CLIL in the context of Vietnam has recently been promoted as a means of tackling the country’s ineffective English language education and upholding its science, technology, engineering, and mathematics fields. This study was conducted to gather information on the teaching of mathematics in English in Vietnamese high schools. Data were collected from a survey and follow-up interviews at 42 high schools across the country. The survey involved 39 school administrators, 78 teachers, and 500 students who had direct experience with teaching and learning mathematics in English while the follow-up interviews were conducted with 14 school administrators and 35 teachers. Statistical analyses performed indicated that CLIL-practising schools in Vietnam performed rather satisfactorily in terms of assessing CLIL learning outcomes and using content and pedagogies appropriate for their CLIL objectives and their school context. CLIL mathematics activities were perceived to be less satisfactory than other CLIL teaching and learning aspects due to practical conditions that constrained the range and diversity of CLIL mathematics activities. Vietnamese schools reported tailoring their CLIL mathematics teaching and learning to suit their particular school settings, which could be seen appropriate at the current early stage of CLIL mathematics implementation in Vietnam. The heavy dependence on foreign-imported curriculum and textbooks, however, still posed challenges in creating meaningful learning outcomes for CLIL students in Vietnam.

Keywords: Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL), CLIL Mathematics, Content-based Instruction (CBI), Competency-based Education, Learning Outcomes

1. Introduction

Content and Language Integrated Learning (or CLIL) refers to an educational approach where “a foreign language is used as a tool in the learning of a non-language subject in which both language and the subject have a joint role” [1]. CLIL distinguishes itself from content-based instruction (CBI) or from the teaching of a content subject in a foreign language (for example, the “English as a Medium of Instruction” or EMI approach) as it has a dual focus on developing the subject-matter knowledge and the foreign language proficiency for students simultaneously [2,3]. CLIL’s principles are grounded on exposing students to rich language input and authentic learning situations so that students can advance their cognitive, communicative, and intercultural competencies [4]. Multiple benefits of CLIL to students’ content and language development in comparison with non-CLIL approaches are recognised in the literature [for example, 5,6-13]. Many education systems around the world have, therefore, enforced the implementation of CLIL as a means of improving their foreign language education or strengthening multilingualism in their society. CLIL, for example, is strongly advocated by European leaders to create economic cohesion, mobility, and cultural diversity among European nations [14]. Additionally, it acts as a cost-efficient means of providing language instruction to students in large classes for many countries in South America and Africa [15-18] and accordingly serves to lessen social and ethnic inequalities [19]. CLIL in the context of Vietnam has been positioned and promoted primarily among responses to the country’s English language education crisis which has widely been addressed in media coverage and scholarly publications [as in 20]. However, the importance of CLIL has been increasingly highlighted as Vietnam now recognises its economic future lies in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) fields and is collaborating with international education organisations to build its STEM education [21,22]. The facilitative policy environment in Vietnam has fuelled CLIL implementation in both general education and the higher education sector [23]. For example, in 2008, Vietnam’s Ministry of Education and Training (MOET) launched the National Foreign Language Project 2020, aiming for English to be the language of instruction in 15% of mathematics classes in well-resourced high schools, particularly in high schools for the gifted [24]. CLIL subjects, originally confined to mathematics, are expected to be expanded to physics, chemistry, biology, and computer science under this initiative [25]. Mathematics and natural science subjects are believed to be appropriate for Vietnam’s new introduction of CLIL since the English language required to teach and learn them is generally unambiguous, precise, and logical [26]. The implementation of CLIL mathematics, in particular, is expected to dually benefit the teaching of mathematics and English – the subjects which hold a very important status in Vietnam’s general education across all school levels – and help redress Vietnam’s present problems in English language teaching

[27].

This paper is part of a doctoral research project conducted between 2016 and 2020 that investigated the implementation of CLIL mathematics at Vietnamese high schools and, from then, trialled relevant management and pedagogical strategies to promote effective CLIL mathematics instruction. Within the scope of this paper, major aspects in the administration and teaching of CLIL mathematics at the Vietnamese high school were explored and reported. The paper first reviews relevant literature to distinguish different approaches to integrating content and language in the school curriculum. From then, it identifies the key components under CLIL mathematical literacy for the context of the Vietnamese high school. The paper presents the quantitative measures taken to collect and analyse data to cast light on the extent to which teaching and administration at the Vietnamese high school cater to the development of students’ CLIL mathematics competencies.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) as an Educational Approach

CLIL as an educational approach has been strongly promoted since the mid-1990s by the Council of Europe in order to enable European citizens to master at least two EU member languages in addition to their first language [28]. CLIL takes different forms and models, originally due to the wide range of bottom-up local initiatives across EU member countries and more recently due to the varied interpretations of CLIL to suit implementation conditions and demands at the local level [3]. Coyle [29] estimates that there are around 216 CLIL versions across educational systems in the world and these differ from one another in terms of focus, students’ starting age, entry linguistic levels, or durations. Therefore, under a broad definition, CLIL subsumes educational approaches that give a dual focus to the content matter and the foreign language in which the content is taught [30]. Approaches to CLIL are classified according to the intended outcomes. Bentley [31], for example, categorises CLIL into soft, mid-way, and hard CLIL. Under the soft CLIL approach, educational content and topics are taught as part of a

language course with the primary aim of helping students to improve their foreign language capacity. Mid-way CLIL, meanwhile, is a subject-led approach of teaching a non-language content in the target language for a certain number of hours. Hard CLIL is achieved when a major part of the mainstream curriculum is delivered in the target language.

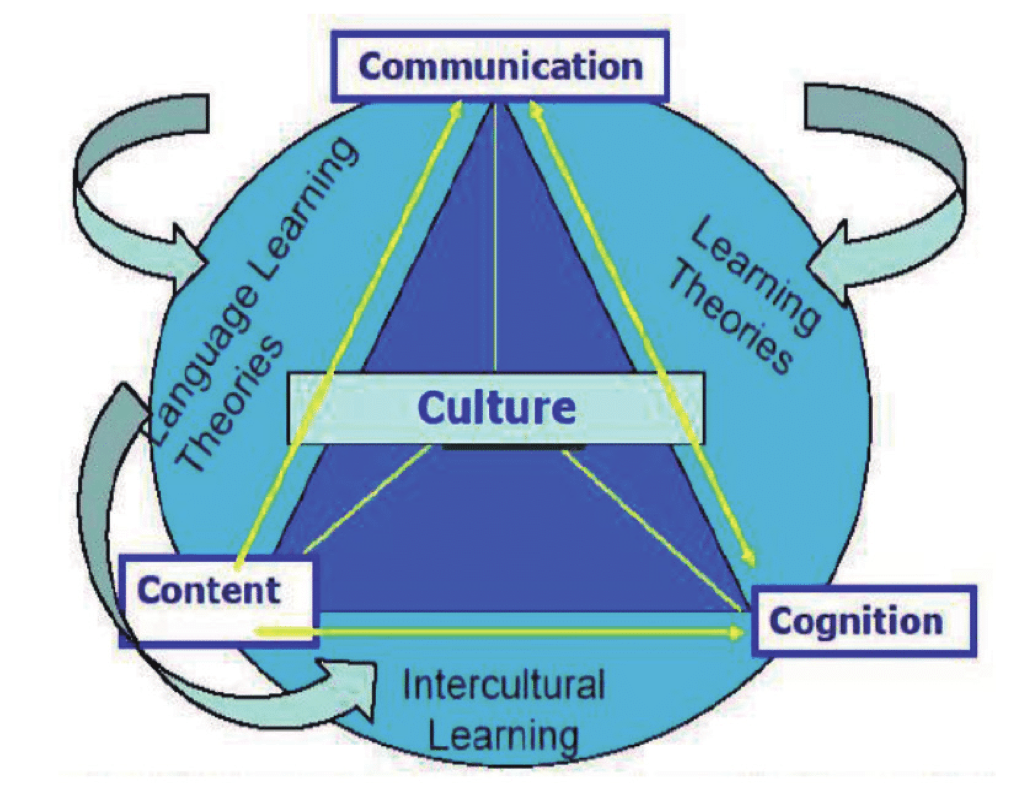

With regard to the language aspect, CLIL is expected to develop for students all the four language skills, namely listening, reading, writing, and speaking. The first two skills are often referred to as receptive language skills and the latter two as productive language skills. CLIL lessons are not sequenced based on grammatical topics; instead, they are informed by and oriented towards lexical topics relevant to the content topics being presented [3]. With regard to the content aspect, CLIL is built into the mainstream curriculum where CLIL students are exposed to a specific subject’s content in the same way they are learning the subject in their first language. CLIL is not about simply learning about topics of general interest [3] and this helps distinguish CLIL from purely language-targeted approaches. By integrating the content and the language aspects, CLIL is identifiable with four key elements – content, communication, cognition, and culture [14] (Figure 1) – and unites learning theories with language learning theories and intercultural understanding. This conceptual framework of CLIL is believed to help CLIL yield success as documented in various studies.

2.2. CLIL Research in Vietnam

CLIL research in Vietnam is limited but has covered different aspects in relation to the administration and teaching of CLIL in the Vietnamese school. A number of doctoral studies have been conducted and have found positive contribution of CLIL to Vietnamese students’ content and language competencies [for example, 33,34-37]. In a review of the challenges facing CLIL-practising schools and teachers in Vietnam, Nhan [27] points to the lack of qualified CLIL teachers and standardised curriculums and also addresses the socio-linguistic challenges to CLIL students.

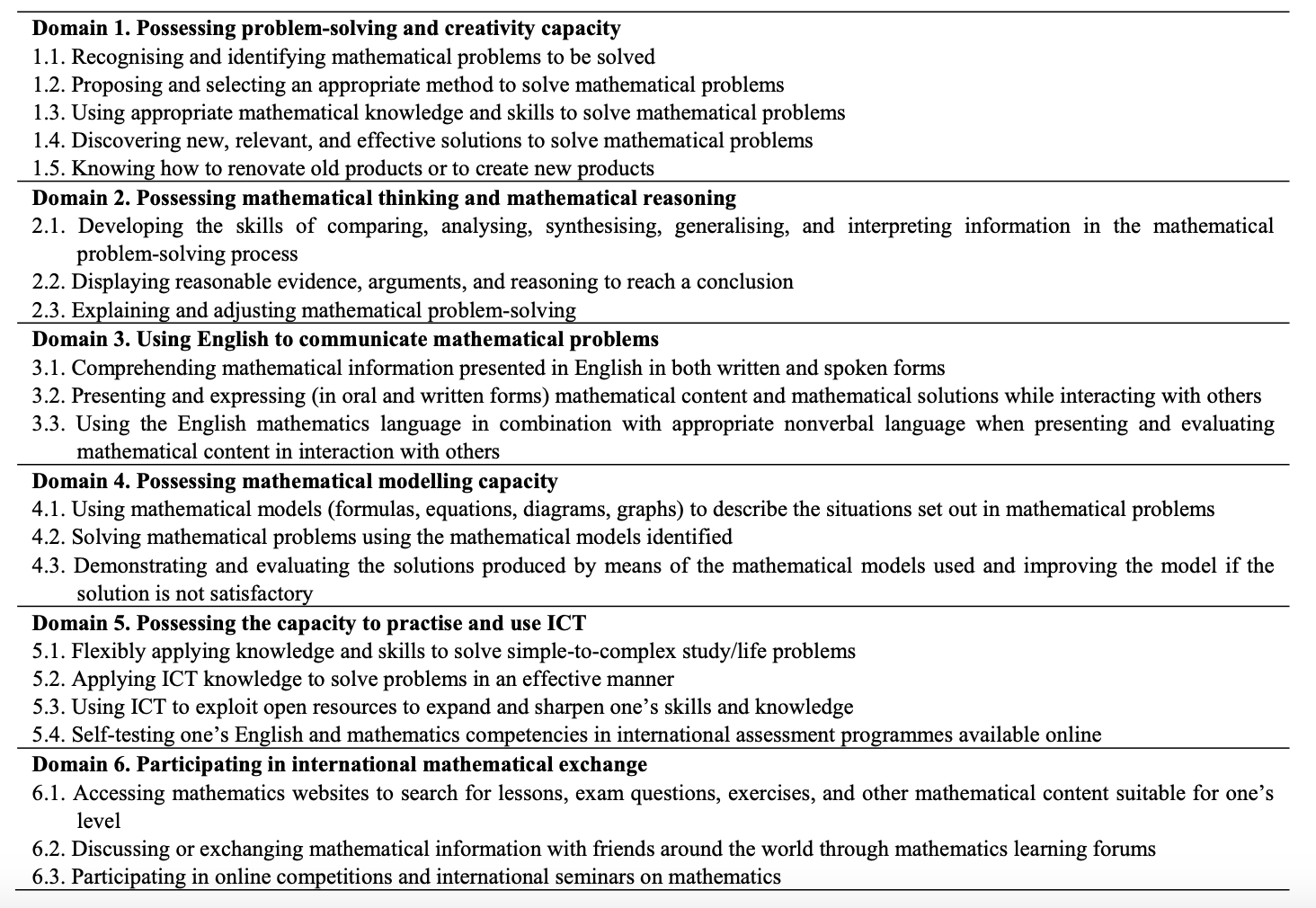

Regarding CLIL’s policy environment, CLIL is much advocated and pushed forward by the government and education-governing bodies. However, this is done more in a motivational than a functional manner. Frameworks for curriculum development, agendas for teacher training and teacher professional development, guidelines for CLIL content and assessing CLIL learning outcomes are almost absent, except for several training materials from MOET [for example, 38]. Drawing on the literature and considering the particular context of mathematics and English teaching and learning in the Vietnamese high school, this study identified the key competencies of CLIL mathematics literacy for Vietnamese high school students to span over six domains

and operationalise into 22 indicators (Table 1). These domains and indicators were consulted with CLIL mathematics teachers and experienced school educators to ensure their currency and validity for the context of Vietnam. Since CLIL mathematics is a combination of mathematical literacy and English language proficiency, CLIL mathematics teaching needs to be positioned within the CLIL pedagogical framework while at the same time must promote learner-centredness and active learning.

3. Methods

3.1. Research Sites and Sampling

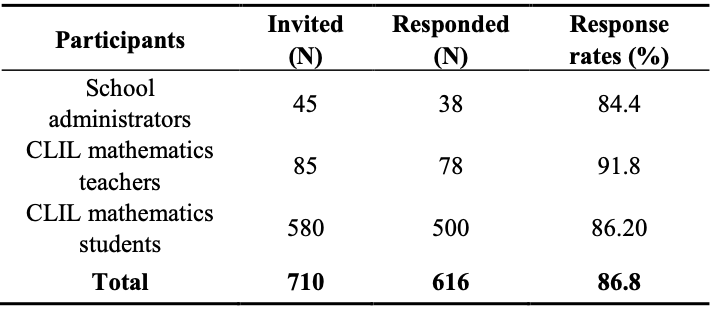

This study involved inclusively all 42 high schools in Vietnam where mathematics instruction was delivered in English as part of the school mathematics curriculum. The surveyed sites represented all the geographical regions of Vietnam, comprising 7 schools based in the northern midlands and northern mountains, 3 in Hanoi Capital City, 14 in the Red River Delta, 10 in the central highlands, 5 in Ho Chi Minh City, and 3 in the southern region. Questionnaires were distributed to the participating schools between July 2018 and November 2018. Responses were received from a total of 616 respondents with details of the sampling and response rates provided in Table 2. Follow-up interviews were conducted with school administrators and CLIL mathematics teachers to cast light on certain aspects in the delivery of CLIL mathematics instruction. Due to practicality reasons, arrangements for interviews were made with only half the number of the administrators and teachers who responded to the survey, namely 14 school administrators and 35 teachers. Efforts, however, were made to ensure that at least one representative from each of the 42 surveyed schools participated in the follow-up interviews for the study to have a complete and broad picture of CLIL implementation in CLIL-practising high schools across Vietnam.

3.2. Research Instruments

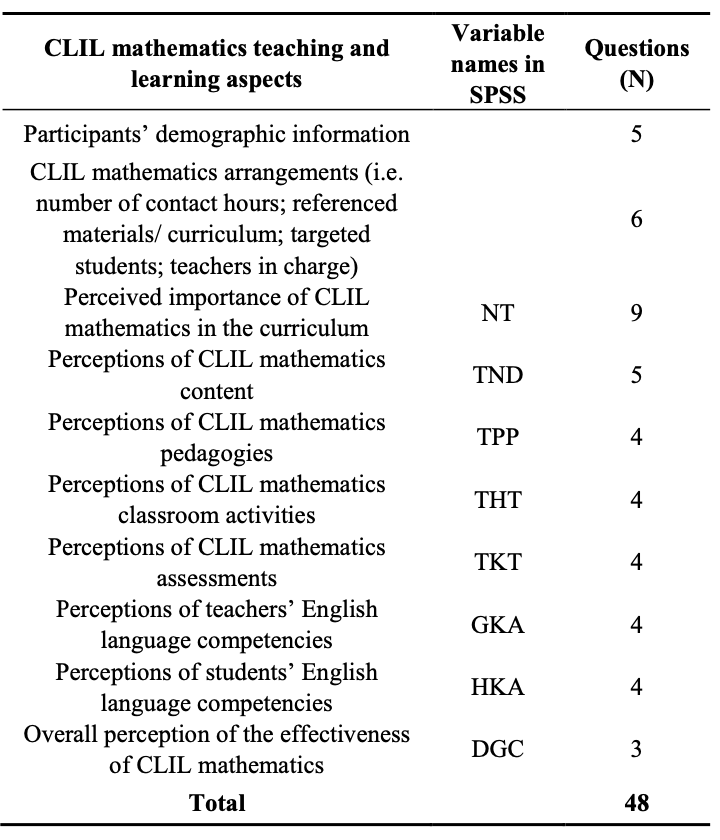

Data for the study were collected using a survey and some follow-up interviews with the research participants. The survey was administered to examine the current situation of CLIL mathematics teaching in the Vietnamese high school setting. Two sets of questionnaires were used to explore seven aspects of CLIL mathematics teaching, namely (a) teaching objectives, (b) teaching content, (c) teaching pedagogies, (d) educational materials and resources, (e) teaching and learning activities, (f) assessments of learning outcomes, and (g) educational environment for CLIL. One set of questionnaires was designed for school administrators and CLIL mathematics teachers; the other was designed for CLIL mathematics students. The questions in both sets of questionnaires were arranged from general demographic to Likert-type questions seeking the perceptions of administrators, teachers, and students regarding how effectively CLIL mathematics was implemented at their school. For Likert questions, respondents were asked to rate their answers on a 5-point Likert scale to indicate the effectiveness of CLIL mathematics teaching and learning at their school (1= very poor, 2 = poor, 3 = average, 4 = good, 5 = excellent). The coding and the number of questions corresponding to each CLIL mathematics teaching aspect are given in Table 3.

Interviews with selected school administrators and CLIL teachers were conducted following the survey. Interview questions centred on the following aspects of CLIL implementation, namely (a) CLIL status and the overall quality of CLIL implementation, (b) achievements and challenges in teaching CLIL mathematics, and (c) achievements and challenges in managing and

administering the teaching and learning of CLIL mathematics. Participants were encouraged to elaborate on aspects of CLIL teaching and learning raised in the survey.

3.3. Data Analysis

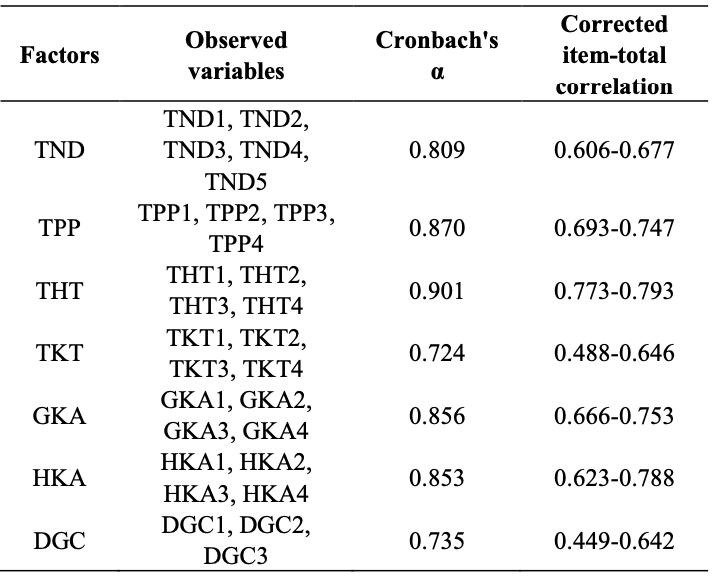

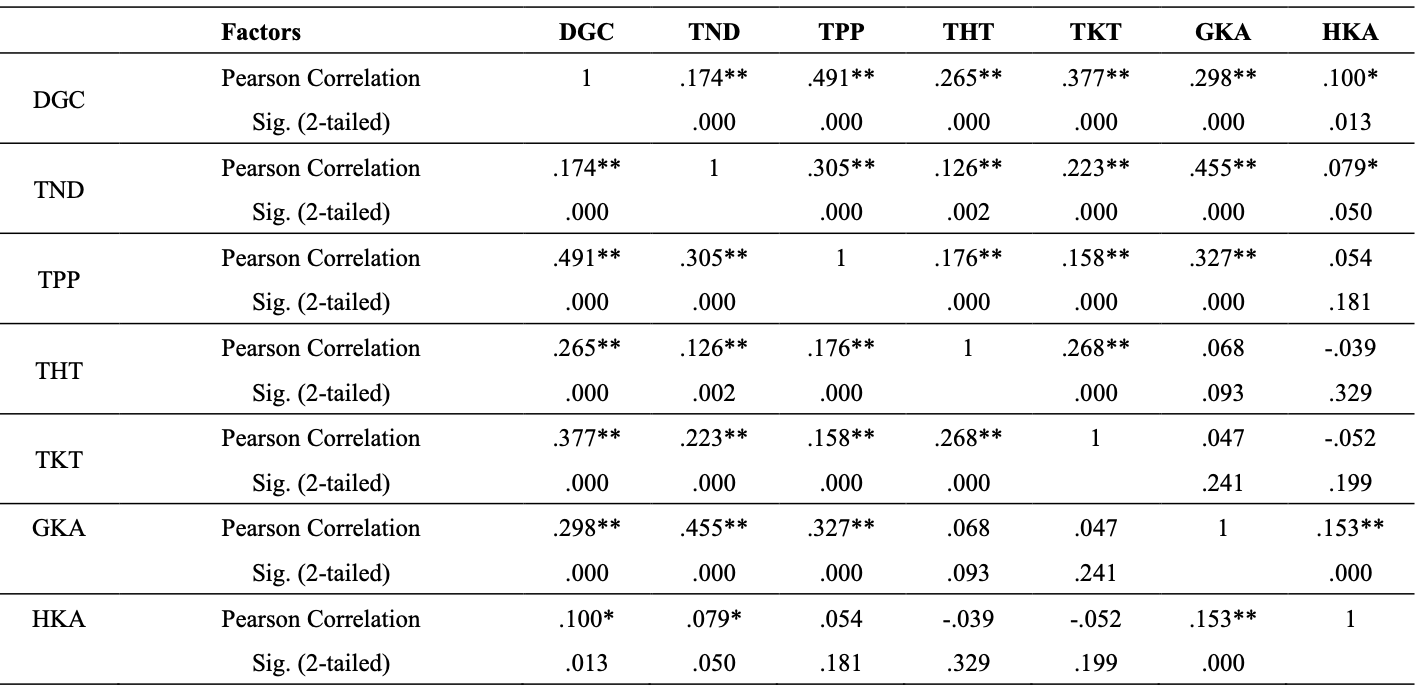

Responses from the survey were coded and entered in SPSS Version 20 and checked for reliability using Cronbach's α reliability and corrected item-total correlation estimates. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA), independent samples test, and one-way ANOVA analyses were used to check the correlation between the variables and to identify the impacts of certain factors, for example, schools’ geographical characteristics and respondents’ roles, on the responses. As can be seen in Table 4, a high reliability coefficient was achieved, with the Cronbach's α reliability estimates ranging from 0.724 to 0.901. The corrected item-total correlation estimates ranged between 0.449 and 0.793 (>0.3) (Table 5), indicating good correlations and reliability of the variables. EFA analysis for 25 independent variables showed Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) test = 0.704 (0.5 KMO 1), Sig Barlett’s Test = 0.00 (< 0.05), and Eigenvalue = 1.405 ( 1), allowing the study to identify the six most important factors in the implementation of CLIL, namely (a) content and materials (TND), (b) teaching pedagogies (TPP), (c) class activities (THT), (d) assessments (TKT), (e) teachers’ English language proficiency (GKA), and (f) students’ English language proficiency (HKA). Relevant findings will be presented in the Finding Section of this paper. Interview data, meanwhile, were entered in NVIVO and coded by themes which corresponded with achievements and challenges in the teaching and learning dimension and the management and administration dimension of CLIL implementation.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. CLIL Content and Materials

While the curriculum from primary to high schools in Vietnam is known to be highly homogeneous under MOET’s centralised authority [39], this study found that Vietnamese high schools differed noticeably in selecting the syllabus and materials for their CLIL mathematics. Schools reported using a range of locally developed and foreign imported syllabi and materials for teaching mathematics in English. To be specific, 28.57% of the schools used the syllabus from MOET; 26.19% developed their in-house mathematics CLIL syllabus; 11.9% used a syllabus and materials from an educational service partner; 9.53% adopted the whole-package syllabus and textbooks currently used at American, UK, Australian, or Singaporean high schools; and the remaining 23.81% used a combination of different sources for their CLIL mathematics content.

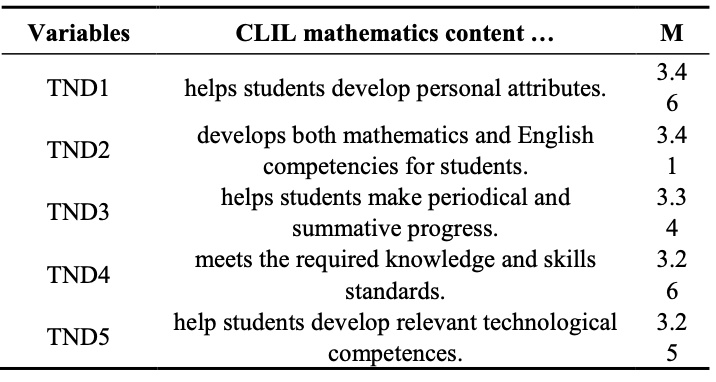

When asked about the relevance and usefulness of the CLIL mathematics syllabus and resources currently in use at their school, the respondents gave an average rating of 3.26 to 3.46 on a scale of 5 (Table 6). School administrators, teachers, and students generally perceived the current CLIL mathematics content to meet the state’s required standards (MTND4=3.26). CLIL mathematics content was perceived to contribute rather positively to the development of students’ personal attributes (MTND1=3.46), with around 45% of the respondents selecting this as an aspect done well or very well at their school. CLIL instruction was also rated by 40% of the respondents as sufficiently developing for students both mathematical and English competencies. 35% of the respondents considered the CLIL materials and syllabus at their school to be appropriate for students to progress in both formative and summative terms. However, the mean scores slightly above the median score of 3, at the same time, indicate that a large number of the respondents took a rather neutral stand regarding the usefulness of CLIL mathematics content. For each of the four CLIL content aspects in Table 5, the percentages of the respondents who gave a rating of 3 ranged between 50% and 70%.

CLIL mathematics activities were rated slightly above average when it came to embedding technologies in lessons and developing relevant technological competencies for students (M=3.12). The participants observed that students were provided with opportunities to explore ICT-supported CLIL content and multimedia and practise with online CLIL resources. Several schools claimed to have e-resources specially developed and reserved for CLIL mathematics, with which students could track their progress and explore international mathematics assessments. However, it should be noted that schools with such capacity received strong support and funding from the government or an affiliated university and were limited in number. The remaining schools primarily identified ICT with in-class Internet, videos, and PowerPoints. On one hand, this was perceived to have resulted in positive changes in students’ attitudes towards ICT and in the way they engaged with the content and interacted with their peers. School administrators and teachers, on the other hand, were hesitant regarding whether students could further develop their ICT-related competencies merely from their CLIL mathematics experience. They argued that this was much dependent on students’ ability to afford ICT access and ICT support either outside CLIL class hours or at home.

Follow-up interviews revealed that well-resourced and urban schools were generally in a better position than suburban schools in developing their CLIL content or select suitable CLIL materials from readily available CLIL resources. Several schools that affiliated with Vietnam’s top universities claimed to use CLIL mathematics content that had been designed and validated to suit their school context with the support from those affiliated universities. At these schools, CLIL mathematics content was categorised into modules, for example, algebra, arithmetic, or geometry, strengthened with vocabulary-building or classroom-communication strategies in English. Schools that grounded their CLIL mathematics teaching on some forms of research were more confident about supplying their CLIL students with meaningful and rich CLIL experience. Less-resourced schools, in contrast, reported building on their mathematics teaching experience and navigating intuitively in developing or selecting suitable CLIL materials. For these schools, foreign materials or syllabi selected, for example, the Montgomery College Mathematics Enrichment Program, Cambridge Mathematics, or Australia’s Canley Vale High School Mathematics Programme, were more often selected out of practicality reasons than from a thorough, systemic, and scrutinised evaluation of available resources. There were concrete benefits from “borrowing” an established foreign curriculum. This, however, was also noted as a challenge for schools in maintaining the mathematics and English content to ensure CLIL students were as prepared to take the standardised high school exit exam in Vietnamese

4.2. CLIL Mathematics Teaching Pedagogies

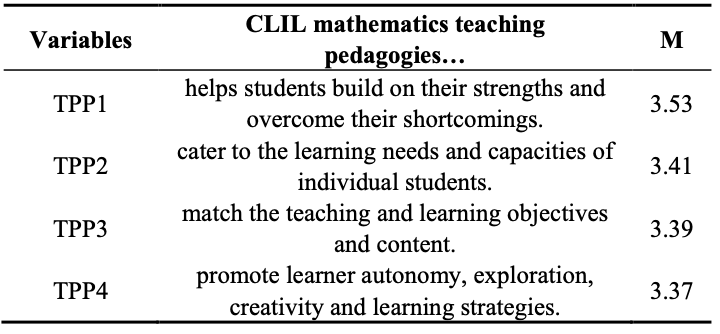

Similar to the content aspect, CLIL mathematics teaching pedagogies were perceived rather positively by school administrators, teachers, and students. The mean ratings for the four CLIL pedagogical aspects reported in Table 7 are halfway between the median score of 3 and the “good” score of 4, indicating that CLIL pedagogies, in general, were compatible with schools’ CLIL objectives and educational activities. Rated highest among aspects of CLIL pedagogies was CLIL teachers’ capacity to help students build on their strengths and overcome their shortcomings (MTPP1=3.53). 50% of the respondents felt their school had done well or exceptionally well in this regard. The pedagogies used in CLIL mathematics teaching were also recognised as having catered to individual students’ learning needs and capacities (MTPP2=3.41) and motivating students to become independent and creative learners (MTPP4=3.37). Around 40% of the respondents rated these two CLIL pedagogical aspects as being done well at their school. CLIL, with it inherent characteristics of blending mathematics with English content, was believed to have the natural advantage of authentic, practical, and contextualised language use. This allowed CLIL teaching pedagogies to naturally lend themselves to engaging students in an experiential and personalised learning experience. Equally important was the respondents’ recognition that CLIL mathematics pedagogies matched the teaching and learning content to achieve targeted outcomes (MTPP3=3.39).

pedagogies

At the time of the survey, CLIL mathematics at the majority of Vietnamese high schools was still in its infancy. The expectations of many schools were mostly to trial and familiarise teachers and students with the CLIL approach. For such purpose, CLIL mathematics at these schools tended to characterise soft CLIL or mid-way CLIL. According to the administrator and teacher interviewees, teachers were considerate of students’ ability to comprehend the mathematics content in English and adjusted their instruction accordingly. For students with a lower level of English, in-class instruction was given in both Vietnamese and English to ensure students understand key mathematics concepts. Attention was also paid to guiding students to pronounce words correctly or use grammar and vocabulary appropriately. Mathematics homework was then given in English with the expectation that students could do some research and further explore relevant CLIL content independently or with their peers before receiving in-class feedback from their teachers in the next class. For students with greater confidence in English, most classroom instruction was given in this target language except for occasional cases when miscommunication might occur and demand the translation of the content into Vietnamese. In class, students took notes, solve mathematics problems, or present their answers and thoughts in English. Apparently, all CLIL-practising schools desired to move to the hard-CLIL version, yet this was challenged by currently unaddressed CLIL teacher-education and resource difficulties.

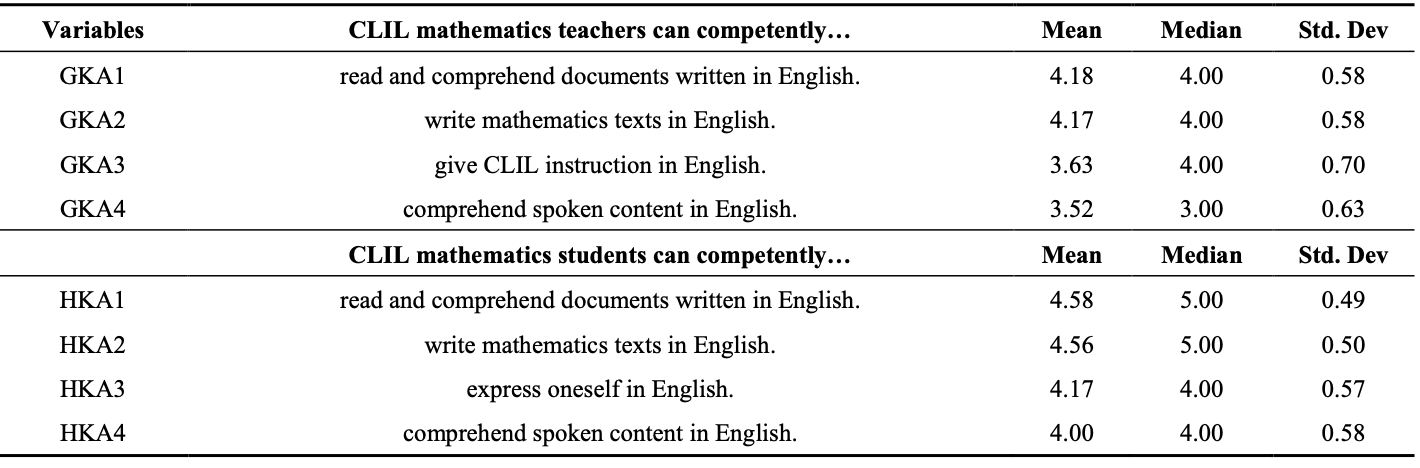

The extent to which teachers could effectively perform their teaching duties was significantly affected by their English language proficiency and the CLIL pedagogical training they received. In the survey, the respondents were asked to rate how teachers’ and students’ levels of English were adequate for their mathematics teaching or learning in English (Table 8). It was interesting to note that students were perceived to outperform teachers in all the four English skills – listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Students’ skills of reading and writing in English were particularly perceived to be strong and adequate for their CLIL undertaking. Teachers, meanwhile, were challenged by the ability to comprehend spoken English and instruct in English. Further one-way ANOVA tests showed that the issue with teachers’ levels of English was most noticeable in the disadvantaged Central Highlands area. Interviews with teachers cast light on the fact that many CLIL mathematics teachers were selected from experienced and respected mathematics teachers who had not necessarily been trained in English. Many of these teachers were trained in Russian at the time when Vietnam was in a tight relationship with the Soviet block or trained in French during French colonisation in the country. Younger CLIL teachers might be better trained in English, but it was often General English for communication purposes rather than English for CLIL teaching that they received training on. This is an issue

that is well aware by MOET and teacher trainers [38] and has been raised in the media since the early introduction of CLIL in Vietnam [40].

Also relevant to CLIL teaching pedagogies, the respondents were asked to name the types of student-led activities in the CLIL mathematics classrooms. As can be seen in Figure 2, the most frequently used activities were drill worksheets, question and answer, and oral presentations, which together accounted for 62.8% of the range of the activities used. While these activities were student-led, they were treated as traditional, old-fashioned rather than student-centred teaching and learning. Many teacher interviewees argued that since the teaching and

learning in the target language was a challenge, resorting to familiar classroom arrangements was often chosen as a time-saving option. The shared agreement among administrators and teachers, however, was that CLIL mathematics teaching needed to switch to a student-centred approach, firstly by increasing project-based or problem-based learning. From the survey, schools based in the two major municipalities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, were found to be doing better in this regard (M=3.7 and M=3.6 respectively) than schools in the Central Highland and the Northern Midlands (M=3.2 and M=3.2 respectively).

4.3. CLIL Mathematics Teaching and Learning Activities

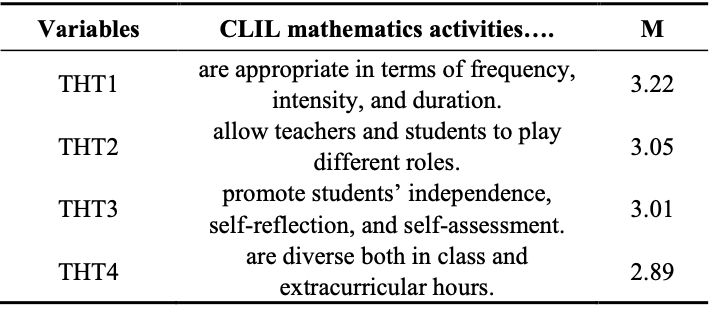

To distinguish with the content aspect discussed in Section 4.1, this section reports findings relevant to the range, diversity, and relevance of CLIL mathematics activities. The mean scores in Table 9 clustered more closely around the median score of 3 and were lower than the mean scores for other CLIL aspects previously presented, indicating that CLIL mathematics activities

were perceived to be less effective than other aspects. Among the four criteria in Table 9, the frequency, intensity, and duration of CLIL mathematics activities were rated the highest with a mean score of 3.22. Data from the survey revealed that timetabling differed remarkably among high schools currently practising CLIL.

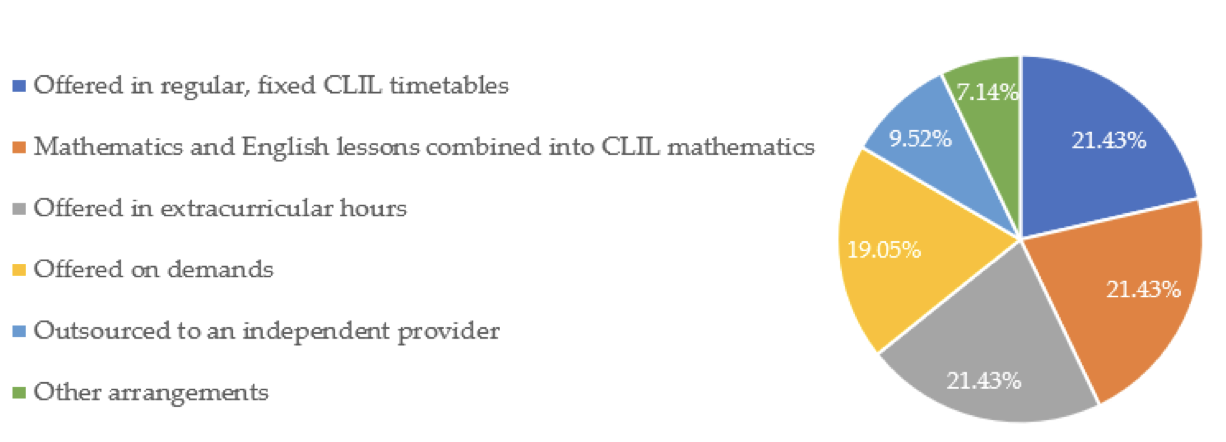

As seen in Figure 3, over a fifth of the schools had regular, fixed timetables dedicated to CLIL mathematics lessons. At these schools, CLIL instruction could constitute up to eight contact hours a week, but most schools could only afford less than two hours of CLIL teaching since the curriculum was already packed and rigid. Other schools either combined mathematics and

English lessons into CLIL mathematics, organised CLIL teaching in extracurricular hours, offered CLIL mathematics only as an elective subject and students could register for CLIL classes on demand, or outsourced CLIL to an independent educational service. The average mean score (MTHT1=3.22) showed that CLIL mathematics activities were, in general, reasonable and suitable for CLIL-practising schools, teachers, and students. Tailoring CLIL mathematics activities to particular school settings rather than applying a “one-size-fits-all” approach for CLIL appears appropriate for the young CLIL implementation in Vietnam.

While CLIL frequency and intensity were rated as reasonable, the rating for CLIL mathematics activities was below average in terms of range and diversity (MTHT4=2.89). There were practical conditions that constrained the diversifying of CLIL mathematics activities. In the survey, 49 CLIL teachers (62.8%) identified the challenges in developing and organising CLIL activities to lie with the small CLIL student cohort. 62 teachers (79.5%) identified the challenges to lie with the small number of contact hours reserved for CLIL mathematics instruction. It should be noted that the rationale behind CLIL varied significantly across schools.

It was often the case that CLIL was taught to students at the top high-performing tier or to those who could afford private CLIL intuition. In particular, half of the schools offered CLIL mathematics to students on demand. Around two-fifths offered CLIL mathematics only to gifted students and a fifth offered CLIL mathematics only to students in mathematics-intensive or English-intensive classes. Only two out of the 42 schools surveyed reported having a schoolwide CLIL policy. The fact that students had to take a highly competitive and high-stakes exit exam in order to graduate from high school and enter a university left schools with little choice other than following the rigid and packed curriculum to prepare students for the exit exam. CLIL mathematics teachers were also assigned to teach non-CLIL mathematics; thereby, the task of diversifying CLIL activities was demanding both in terms of time and resources. CLIL

mathematics, at this stage of CLIL policy implementation, acted more as an add-on than an integrated and essential component in the high school curriculum as desired by MOET and schools. The respondents rated CLIL mathematics activities to be average in terms of allowing students to play different roles (MTHT2=3.05) and become independent, reflective thinkers (MTHT3=3.01). While these two qualities seemed to be concerned with teaching pedagogies, CLIL mathematics activities were perceived to contribute a share. This is particularly since how much students can develop their independent thinking and self-reflection is dependent on the way activities are designed or encourage them to do so. CLIL mathematics materials, whethe imported whole-package from an overseas provider or developed in-house by Vietnamese high schools, were explored primarily from a content and cognitive perspective. There was, therefore, a frequent tendency for students to focus on mental translation of content while the intercultural and communicative functions of CLIL were not adequately attended to.

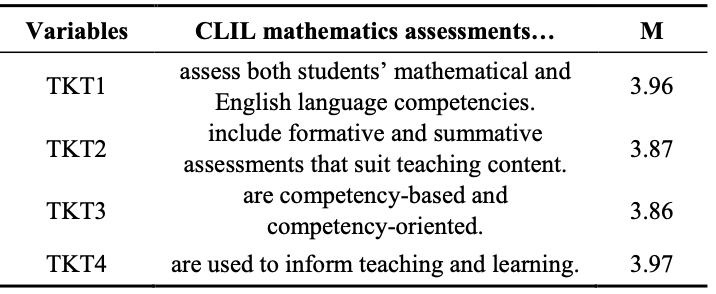

4.4. CLIL Mathematics Assessments

Compared with other teaching and learning aspects, assessing the skills and knowledge that students had gained through CLIL appeared to be an aspect done more effectively by most of the schools surveyed (Table 10). The research participants generally perceived that CLIL assessments were not only able to assess students’ mathematical literacy and their English language proficiency but were also used to inform teaching and learning so that students could make timely adjustments and progress. The average ratings for these two aspects of CLIL assessments were almost 4. Out of 616 respondents, around 500 believed that CLIL assessment activities at their school did well or exceptionally well in these regards (MTKT4= 3.97 and MTKT1= 3.96, respectively). CLIL practitioners also reported using both formative and summative assessments to suit each teaching content (MTKT2=3.87). This was despite the fact that formative assessments are a rather recent educational strategy in Vietnam and its presence in the Vietnamese school system has been much challenged due to the country’s various structural-cultural obstacles, including its heavily exam-oriented practice [41,42]. Several schools in Vietnam’s two major cities, Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City, were funded to have their CLIL students take the mathematics exam papers endorsed by a foreign provider, for example, the UK’s Edexcel multinational examination body. The last aspect regarding CLIL assessments practices in the survey concerned whether CLIL assessments were grounded on a competency approach. 491 out of the 616 respondents surveyed believed that their schools did well in collecting evidence and making judgements about students’ CLIL mathematics achievements (MTKT3=3.86).

assessments

CLIL mathematics assessments were facilitated by a number of conditions and policy factors. First and foremost, Decision 72/2014-QĐ-TTg dated December 2014 by Vietnam’s Prime Minister allows schools to award bonus marks to CLIL students. CLIL mathematics assessments are optional, so CLIL students who achieve a pass mark in their CLIL assessments will receive bonus marks towards their mathematics results. This was seen by school administrators and teachers to have encouraged students to work hard on their mathematics tests in English. Secondly, CLIL mathematics assessments at many Vietnamese schools were informed by international mathematics assessments such as Cambridge IGCSE Mathematics, Cambridge A/AS Level Mathematics, the standardised college admission test (SAT) run by the U.S. College Board, or the English Baccalaureate (EBacc). These assessments are competency-based, therefore being useful for Vietnamese CLIL teachers in developing competency-based content and competency-based teaching approach. Quite a number of students from CLIL mathematics classes were found to plan for their study overseas. CLIL assessments that align to international benchmarks then carry practical and meaningful values. It should be noted that since most CLIL students in this study were gifted students or were receiving intensive mathematics and English instruction, they tended to have a better aptitude to succeed in CLIL compared with non-CLIL students.

Overall, the findings from this study indicated that Vietnamese high schools performed rather satisfactorily in terms of assessing CLIL learning outcomes and using content and pedagogies appropriate for their CLIL objectives and their school context. CLIL mathematics activities were perceived to be less satisfactory than other CLIL teaching and learning aspects due to practical conditions that constrained the range and diversity of CLIL mathematics activities.

5. Conclusions

After over 10 years of implementation, CLIL mathematics has started to establish for itself a role in Vietnam’s general education system. It is, at the same time, in the process of negotiating and identifying its own pathway from available CLIL models and practices. Vietnamese high schools are rather responsive to the government’s CLIL policy and have undertaken certain self-initiative in terms of curriculum, teaching staff, and resources to shape a CLIL approach that suits their context. Given the practical constraints in terms of resources and policy guidelines for CLIL, what Vietnamese high schools have managed to achieve so far is reasonable and promising. This is the acknowledgement shared by school administrators, teachers, and students

who were surveyed or interviewed in this study.

However, from the perspective that implementing CLIL means significant changes in the way teaching is planned, sequenced, and implemented, CLIL mathematics in Vietnam has not gone very far from integrating linguistic and non-linguistic materials. Vietnamese high schools still depend heavily on the materials and syllabus that are primarily developed and used for multilingual and bilingual contexts in the English-speaking world. While this allows the Vietnamese CLIL mathematics curriculum to align with international standards, the Vietnamese context of English language use, the Vietnamese socio-cultural norms, and the psychological, cultural, and cognitive needs of Vietnamese high school students are different. This has important implications regarding localising CLIL content and pedagogies. CLIL mathematics in Vietnam will also benefit from training CLIL teachers and upholding teachers’ capacity so that the potential of CLIL will be optimised.

REFERENCES

[1] D. Marsh. CLIL/EMILE the European dimension, University of Jyväskylä, Jyväskylä, 2002.

[2] K. Graham, Y. Choi, A. Davoodi, S. Razmeh, L. Dixon. Language and content outcomes of CLIL and EMI: A systematic review, LACLIL, Vol.11, No.1, pp. 19-37, 2018, doi:10.5294/laclil.2018.11.1.2.

[3] H. Brown, A. Bradford. EMI, CLIL, & CBI: Differing approaches and goals. In Transformation in language education, A. Krause, H. Brown, Eds. JALT, Tokyo, pp. 328-334, 2017.

[4] D. Coyle. Content and Language Integrated Learning: Towards a connected research agenda for CLIL pedagogies, The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Vol.10, pp. 543-562, 2007.

[5] H. Binterová, V. Petrásková, O. Komínková. The CLIL method versus pupils' results in solving mathematical word problems, The New Educational Review, Vol.38, No.4, pp. 238-249, 2014.

[6] A.C. Alonso. Receptive vocabulary of CLIL and Non-CLIL primary and secondary school learners, Complutense Journal of English Studies, Vol.23, pp. 59-77, 2015.

[7] J. Coral, T. Lleixà, C. Ventura. Foreign language competence and content and language integrated learning in multilingual schools in Catalonia: An ex post facto study analysing the results of state key competences testing, International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Vol.21, No.2, pp. 139-150, 2018.

[8] J. Goris, E. Denessen, L. Verhoeven. Effects of the Content and Language Integrated Learning approach to EFL teaching: A comparative study, Written Language & Literacy, Vol.16, No.2, pp. 186-207, 2013.

[9] A. Lázaro. Faster and further morphosyntactic development of CLIL vs. EFL Basque-Spanish bilinguals learning English in high-school, International Journal of English Studies, Vol.12, No.1, pp. 79-96, 2012.

[10] F. Lorenzo, S. Casal, P. Moore. The effects of content and language integrated learning in European education: Key findings from the Andalusian bilingual sections evaluation project, Applied Linguistics, Vol.31, No.3, pp. 418-442, 2010.

[11] K. Ouazizi. The effects of CLIL education on the subject matter (mathematics) and the target language, Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, Vol.9, No.1, pp. 110-137, 2016, doi:10.5294/laclil.2016.9.1.5.

[12] M. Xanthou. The impact of CLIL on L2 vocabulary development and content knowledge, English Teaching: Practice and Critique, Vol.10, No.4, pp. 116-126, 2011.

[13] W. Yang. Content and language integrated learning next in Asia: Evidence of learners’ achievement in CLIL education from a Taiwan tertiary degree programme, International

Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, Vol.18, No.4, pp. 361-382, 2015.

[14] D. Coyle, P. Hood, D. Marsh. CLIL: Content and language integrated learning, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2010.

[15] S. Yassin, D. Marsh, O.E. Tek, L.Y. Ying. Learners’ perceptions towards the teaching of science through English in Malaysia: A quantitative analysis, International CLIL Research Journal, Vol.1, No.2, pp. 54-69, 2009.

[16] K. Suwannoppharat, S. Chinokul. Applying CLIL to English language teaching in Thailand: Issues and challenges, Latin American Journal of Content & Language Integrated Learning, Vol.8, No.2, pp. 237-254, 2015.

[17] F.D. Floris. Learning subject matter through English as the medium of instruction: Students’ and teachers’ perspectives, Asian Englishes, Vol.16, No.1, pp. 47-59, 2014.

[18] C.-y. Leung. Content and language integrated learning: perceptions of teachers and students in a Hong Kong secondary school. Hong Kong University, Hong Kong, 2013.

[19] P. Mehisto, D. Marsh, M. Frigols. Uncovering CLIL - Content and language integrated learning in bilingual and multilingual education, Macmillan Publishers, Oxford, 2008.

[20] N.H. Nguyen. National Foreign Languages 2020 Project: Challenges, opportunities and solutions, Australia - Vietnam Future Education Forum, Hanoi, 12 November, 2011.

[21] T. Grant. Vietnam's economic future lies in STEM careers, online learning and public-private partnerships, Outreach, Arizona State University, 4 April, 2017.

[22] British Council. STEM education programme, Retrieved from https://www.britishcouncil.vn/en/programmes/education/sci ence-innovation/newton-programme-vietnam/stem, n.d.

[23] T.B.N. Nguyen. Content and Language Integrated Learning in Vietnam: Evolution of students’ and teachers’ perceptions in an innovative foreign language learning system. Université de Toulouse, Université Toulouse III-Paul Sabatier, 2019.

[24] MOET. Quyết định về việc phê duyệt đề án "Dạy và học ngoại ngữ trong hệ thống giáo dục quốc dân giai đoạn 2008-2020" [Decision on approving Project "Teaching and learning foreign languages in the national education system in the period 2008 to 2010] MOET, Hanoi, 2008.

[25] MOET. Quyết định phê duyệt Đề án phát triển hệ thống trường Trung học phổ thông chuyên giai đoạn 2010-2020 [Decision on approving the Project of developing the gifted

high school system in the period 2008 to 2010], MOET, Hanoi, 2010.

[26] P.C. Nguyen. Teaching mathematics in English: A personal experience perspective, University of Languages and International Studies – Vietnam National University Hanoi, Hanoi, 2010.

[27] T. Nhan. Promoting content and language integrated learning in gifted high schools in Vietnam: Challenges and impacts, Internet Journal of Language, Culture and Society, Vol.38, pp. 146-153, 2013.

[28] A. Llinares, T. Morton, R. Whittaker. The roles of language in CLIL, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2012.

[29] D. Coyle. CLIL-A pedagogical approach from the European perspective. In Second and foreign language education: Encyclopedia of language and education volume 4, N. Van Deusen-Sholl, N.H. Hornberger, Eds. Springer Science+ Business Media, New York, pp. 97-111, 2010.

[30] D. Marsh. Language awareness and CLIL. In Encyclopedia of language and education, N.H. Hornberger, Ed. Springer US, Boston, MA, pp. 1986-1999, 2008.

[31] K. Bentley. The TKT course: CLIL module,Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2015.

[32] D. Coyle. Teacher education and CLIL methods and tools, Centro di Ricerca sull'Educazione ai Media all'Innovazione e alla Tecnologia (CREMIT) Seminar, Milan, Italy, 1 April, 2011.

[33] L.T.K. Vo. Tạo môi trường cho trẻ mầm non làm quen với tiếng Anh qua phương pháp CLIL [Familiarising pre-school students with English through the CLIL approach], Tạp chí Giáo dục [Journal of Education], Vol.8, pp. 198-220, 2017.

[34] P.T. Nguyen. Using the textbook “Practice Maths 1” to teach Maths in English to first graders at Minh Khai 1 primary school – Difficulties and some suggested solutions. University of Languages and International Studies, Vietnam National University Hanoi, 2013.

[35] P.D. Vu, A.T. Le. Teaching mathematics in English to Vietnamese 6th grade students by using content and language integrated learning (CLIL) approach, Vietnam Journal of Education, Vol.5, pp. 41-45, 2018.

[36] T.T. Nguyen. Interactional corrective feedback: A comparison between Primary CLIL in Spain and Primary CLIL in Vietnam. University Autónoma De Madrid, Madrid, 2018.

[37] H.T. Chu. Vai trò của giáo viên trong việc dạy học tích hợp nội dung và ngôn ngữ [Teachers' roles in CLIL classrooms], Vietnam Journal of Education, Vol.423, No.1, pp. 27-31, 2018.

[38] Secondary education sector development program. Tài liệu tập huấn dạy học môn Toán và các môn khoa học tự nhiên bằng tiếng Anh trong trường trung học phổ thông [Training document for CLIL mathematics and natural sciences in high schools], Ministry of Education and Training, Hanoi, 2013.

[39] L. Hoang. Accountability in Vietnam’s education: Toward effective mechanism in the decentralization context. In Background paper for the 2017/8 global education monitoring report. Accountability in education: Meeting our commitments, Global Education Monitoring Report Team, Ed. UNESCO, Paris, pp. 1-17, 2017.

[40] Vietnamnet Bridge. Vietnam lays red carpet to welcome foreign teachers, Vietnamnet, 23 January, 2013.

[41] T. Pham. Implementing formative assessment: An experience learned from Asian classrooms, Australian Association for Research in Education (AARE) conference 2016: Transforming education research, Melbourne, 28 November - 1 December, 2016.

[42] T. Pham, P. Renshaw. Formative assessment in Confucian heritage culture classrooms: activity theory analysis of tensions, contradictions and hybrid practices, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, Vol.40, No.1, pp. 45-59, 2015.

- Professional skills development for University lecturers: A case study in the Mekong Delta region of VietnamNghiên cứu10/06/2025

- Management of primary teacher training programs using the CDIO approach: Theoretical frameworks and practical implementationsNghiên cứu03/06/2025

- Nghiên cứu mối liên quan giữa tật cận thị và một số yếu tố khác với tình trạng lo âu của sinh viên 2 năm đầu đại họcNghiên cứu22/05/2025

- Mối liên quan giữa tình trạng lo âu với tật cận thị và một số yếu tố khác của sinh viên năm cuối đại họcNghiên cứu13/05/2025

- Đổi mới quản lý cơ sở giáo dục đại học trong bối cảnh tự chủ đại họcNghiên cứu01/05/2025

- Xây dựng và sử dụng khung năng lực trong phát triển đội ngũ giáo viên làm công tác tư vấn học đường ở trường tiểu họcNghiên cứu07/04/2025

- Tổng quan các nghiên cứu phát triển năng lực số cho sinh viên đại học ngành giáo dục tiểu họcNghiên cứu04/04/2025

- Bản đồ cơ thể đầu tiên về ảo giácNghiên cứu01/04/2025

- Thông tin tuyển sinh ngành Quản lý giáo dục 2025Tin tức30/06/2025

- Thông tin tuyển sinh ngành Tâm lý học giáo dục 2025Tin tức30/06/2025

- THÔNG TIN TUYỂN SINH TRƯỜNG SƯ PHẠM NĂM 2025: KHOA GIÁO DỤC MẦM NONGiới thiệu28/06/2025

- Kỳ thi tốt nghiệp THPT quốc gia 2025 đã hoàn thànhTin tức27/06/2025

- Tài liệu hướng dẫn dành cho thí sinh 2025Tin tức25/06/2025

- Nam sinh có khả năng phục hồi tốt hơn nữ sinh trước những trở ngại trong học tậpTin tức20/06/2025

- Công bố kết quả PISA 2022 của Việt NamTin tức17/06/2025

- Luật Nhà giáo đã được thông quaTin tức17/06/2025