Internal Quality Assurance of Initial Teacher Education Programs in Vietnam: A Descriptive Study

GS.TS. Thái Văn Thành, TS. Phan Hùng Thư

Abstract

This paper seeks to investigate the practices of internal quality assurance in teacher education programs across Vietnam. Survey questionnaires were administered to three groups of stakeholders: teachers/managers, student teachers/alumni, and employers from five teacher education programs. This was done to obtain appraisals of internal quality assurance practices related to their programs. The findings show that the programs have embraced quality assurance in their policies and practices in order to ensure that expected learning outcomes satisfy stakeholder needs. They also show that the program content, instruction, student assessment, staff, and supporting activities achieve the expected learning outcomes. However, the study also suggests that expected learning outcomes should better reflect school requirements and equip future teachers with more practical teaching skills required for effective teaching at schools. To this end, academic and professional components should be integrated and schools should be more involved in training future teachers. In general, it is recommended that quality assurance needs be geared toward improving quality rather than merely conforming to external standards.

Key words: Internal quality assurance, Professional components, Vietnam

Introduction

In recent years, increasing public scrutiny and pressure for accountability has driven higher education institutions to pursue quality assurance. Teacher education, with the crucial role of preparing future teachers for schools, is not an exception. The quality of an education system depends largely on the preparedness of teachers. It has been consistently found that teacher quality is the most significant factor impacting student learning and achievement (Bransford, Darling-Hammond, & LePage, 2005; Harford, 2010; Haycock & Huang, 2001). Research also shows that the quality assurance of pre-service teacher preparation is strongly linked with the quality of future teachers and student achievements (Brennan, 2018; Ingvarson & Rowley, 2017).

Past decades have seen a growing interest in quality assurance for higher education in general and teacher education specifically (both pre-service and advanced) (Chong & Ho, 2009; Cochran-Smith, 2001; Hudson, Zgaga, & Astrand, 2010; Sacilotto-Vasylenko, 2013). Countries have adopted various mechanisms to control, maintain and improve education quality, including internal assurance, accreditation, assessment and auditing (DEEWR, 2008). In Vietnam, higher education institutions have begun to embrace quality assurance as a result of pressure from the government and the public for greater autonomy and accountability (Nguyen, Ta, & Nguyen, 2017; Nguyen, Oliver, & Priddy, 2009; Nguyen, 2017). A variety of QA models have been utilised by higher education institutions in Vietnam to achieve and improve program quality according to national and regional standards. These include ABET, AUN-QA, and MOET (Nguyen et al., 2017; Nguyen & Ta, 2018; Nhan & Nguyen, 2018).

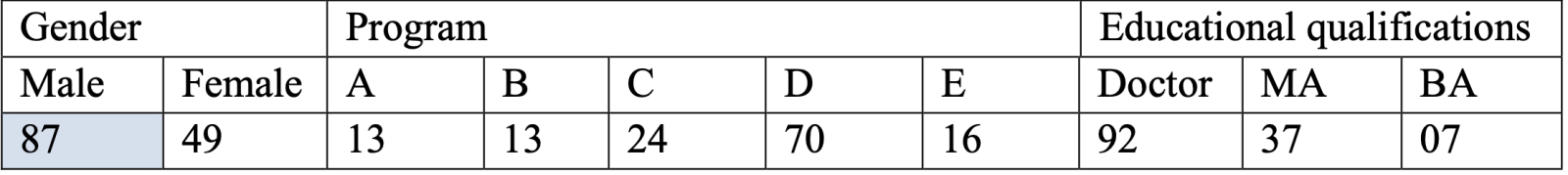

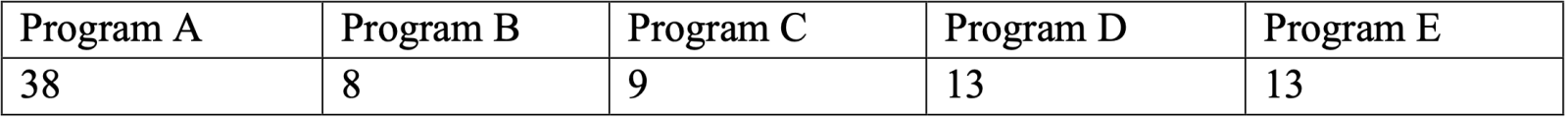

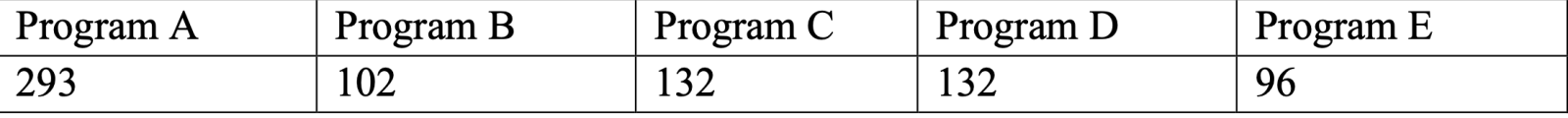

This paper seeks to investigate the practices of quality assurance (QA) through five teacher education (TE) programs across Vietnam. These are long-established programs, each providing education services for a large number of student teachers. Survey questionnaires were administered to three stakeholder groups: teachers/managers, student teachers/alumni, and employers from five TE programs to obtain their appraisals of the QA practices at their programs.

Literature Review

Quality Assurance in Higher Education

It is generally agreed that quality is difficult to define due to its manifold meaning, which is subject to various interpretations by different stakeholders (Harvey & Green, 1993; Martin & Stella, 2007). A literature review by Schindler, Puls-Elvidge, Welzant, and Crawfod (2015) identified four broad conceptualisations of quality: quality as fitness for purpose, excellence, transformation, and accountability. In the first dimension, quality as fitness for purpose is achieved as the mission/vision or goals of a program or institution are fulfilled (Y. Cheng & Tam, 1997; Harvey & Green, 1993; Harvey & Knight, 1996). In the second, quality is viewed as the pursuit of excellence by exceeding a standard (Y. Cheng & Tam, 1997; Harvey & Green, 1993; Harvey & Knight, 1996). In the third, an educational program can be considered high-quality when it has a positive impact on student learning, increases a capacity for personal and professional enrichment, and contributes to socio-economic development (Biggs, 2001; Harvey & Green, 1993; Harvey & Knight, 1996). Finally, quality is associated with the effective and efficient use of resources and the defect-free delivery of products or services (Y. Cheng & Tam, 1997; Harvey & Green, 1993; Harvey & Knight, 1996; Nicholson, 2011). According to Y. C. Cheng (2003), quality is often viewed as fulfillment of planned goals that reflect stakeholder needs and accountability to the public.

The quality of an education program is defined by three components: input (curriculum, resources, facilities, and teaching staff), process (student admission, instruction, assessment, and supporting services) and outcomes (student pass rates, knowledge, skills, disposition, and graduate employability) (Biggs, 2001; Y. Cheng & Tam, 1997; Lagrosen, Seyyed-Hashemi, & Leitner, 2004; Tam, 2010, 2014). Similarly, UNESCO (1998) conceptualises quality in higher education as “a multi-dimensional concept, which should embrace all its functions, and activities; teaching and academic programs, research and scholarship, staffing, students, buildings, facilities, equipment, services to the community and the academic environment.”

Quality assurance can be defined broadly or narrowly based on the view of quality adopted. In a broad sense, quality assurance is often described as “policies and processes directed to ensuring the maintenance and enhancing of quality”. In a more narrow sense, viewing quality as meeting certain standards in addition to achieving institutional goals, Martin and Stella define quality assurance as “policies and mechanisms implemented in an institution or program to ensure that it is fulfilling its own purposes and meeting the standards that apply to higher education in general or to the profession or discipline in particular” (Martin & Stella, 2007, p. 34). Y. C. Cheng's (2003) review of quality assurance in recent decades reports that quality assurance focuses both on internal quality assurance to improve the effectiveness of educational and to ensure that the education services reflect stakeholder needs and are accountable to the public. Common mechanisms for quality assurance include quality audit, assessment and accreditation (DEEWR, 2008; Sanayl, 2013).

There are often two types of quality assurance in higher education: internal and external quality assurance (Learning, 1997). Internal quality assurance refers to the policies and practices that an institution or a program has in place to guarantee that their goals are achieved and certain standards are met. External quality assurance is often used to accredit a program and is conducted by an independent organisation. According to Eurydice (2006), internal evaluation of teacher education in European countries involves various stakeholders, including management, academic staff students, and evaluation experts. Official documents used to establish criteria for the internal evaluation of initial teacher education includes legislation on higher education, regulations on initial teacher education, qualification standards for prospective teachers, standards for external evaluation, and national indicators (i.e. trainers/student ratios, student performances, etc.). Areas of internal quality evaluation in initial teacher education include curriculum content, curriculum structure, teaching methods, assessment practices, staff management, infrastructure, and outcomes (candidate proficiencies in relation to professional standards) (Eurydice, 2006).

AUN-QA Framework at the Program Level

The quality assurance framework used in this study is adapted from the AUN-QA model (AUN, 2015). The framework focuses on quality in three dimensions: input, process, and output. Stakeholder needs are used as the starting points to shape the expected learning outcomes of the program. Curriculum content and structure, teaching and learning approaches, and learning assessment are key components used to translate program goals into outcomes. It is purported that program specification, including expected learning outcomes, curriculum mapping, teaching strategies and assessment, should be made available and accessible to various stakeholders. Curriculum content, instructional strategies, and student assessment in programs should be varied and appropriate in order to achieve learning goals. A quality program is also required to have policies and mechanisms to ensure sufficient, quality support staff to enable the achievement of learning outcomes. In addition, student quality, supporting activities, facilities, and infrastructure are considered important inputs that contribute to the production of quality outputs. Quality enhancement is another key aspect of program quality assurance, which presupposes the ongoing improvement of educational quality through regular review and remedial actions. Benchmarking involves setting performance indicators by referring to peer programs, either domestically or internationally, a strategy that requires educational institutions to constantly upgrade themselves.

Materials and Research Methodology

This study was conducted in five pre-service teacher education programs scattered across Vietnam. All of these programs operate on a large scale and have an established tradition of teacher training. There were 16,000 student teachers in program A; more than 7,500 student teachers in program B; almost 20,000 in program D; and 15,000 in program E. This study utilised a quantitative method that involved the administration of a survey questionnaire to different stakeholder groups. These included teachers/managers; students/alumni; and employers. The questionnaire was designed based on a QA model at the program level, comprising 11 categories as follows:

Expected Learning Outcomes: A process of formulating expected learning outcomes that reflect stakeholder needs (subject to regular review and improvement).

Program Specification: Program information, including expected learning outcomes, curriculum content, teaching strategies, and student assessment is made available and accessible to stakeholders.

Program Content and Structure: The curriculum is designed to achieve the learning goals (subject to regular review and improvement).Teaching and Learning Approach: Instructional activities are varied and appropriate to ensure learning outcomes (subject to regular review and improvement).

Student Assessment: A variety of techniques are used to assess student learning and achievements (subject to regular review and improvement).

Academic Staff Quality: The process of recruiting, promoting, tenuring, and developing academic and supporting staff to ensure quality for obtaining desired learning outcomes (subject to regular review and improvement).

Support Staff Quality: The adequacy and competencies of staff who provide services in libraries, laboratories, computer facilities and student services, as well as policies and practices relating to recruitment, promotion, performance management and career development plans for support staff.

Student Quality and Support: Student intake policies, admission criteria, as well as methods and criteria for the selection of students are in place to ensure quality student input. There is

an adequate monitoring system for student progress, academic performance, and workload. Academic advice, co-curricular activities, student competitions, and other student support services are available to support learning.

Facilities and Infrastructure: Infrastructure and learning resources are adequate to support teaching and learning (subject to regular review and improvement).

Quality Enhancement: Curriculum, instructional approaches, student assessment, quality of support services facilities, and stakeholder feedback mechanisms are subject to evaluation and enhancement.

Output: Student pass rates, dropout rates, and employability are monitored and benchmarked for improvement. Achievement of learning outcomes and employability of graduates are also monitored (subject to regular review and improvement).

The survey questionnaire was administered to three groups of subjects, including 136 teachers and managers, 755 students and alumni, and 81 employers.

Descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations for each item and category, were calculated using SPSS software.

Results

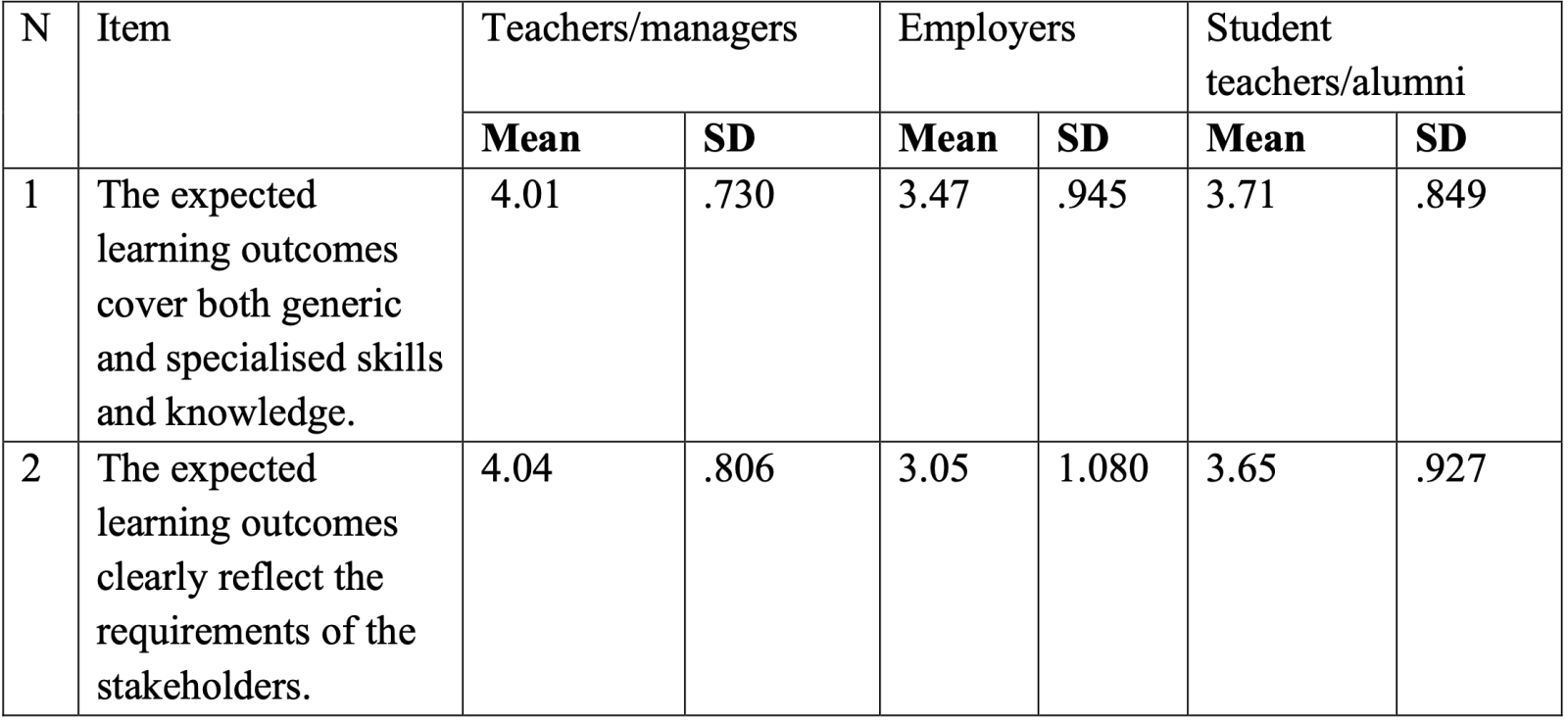

Expected Learning Outcomes

A quality program’ expected learning outcomes, including content knowledge, teaching skills, generic skills and dispositions, should reflect the needs of various stakeholders, including society, the government, employers, learners, and so forth. This should then be translated into the institution’s mission and vision.

The findings show that there is a significant disparity in the perception of teachers/managers and employers in rating the programs’ expected learning outcomes. This is based on the criterion that the expected learning outcomes should reflect stakeholder needs, with average ratings at 4.04 and 3.05 respectively. 84% of the teachers and managers expressed their agreement with the quality assurance in this criterion, compared with 37% of the employers. Similarly, higher proportions of teachers/managers agreed with the statement that expected learning outcomes cover both generic and specialised skills and knowledge compared with employers. Less than half of employers (48%) agreed that there is a balance between generic and specialised knowledge and skills in the program’s outcomes, compared with 70% of the student teachers/alumni

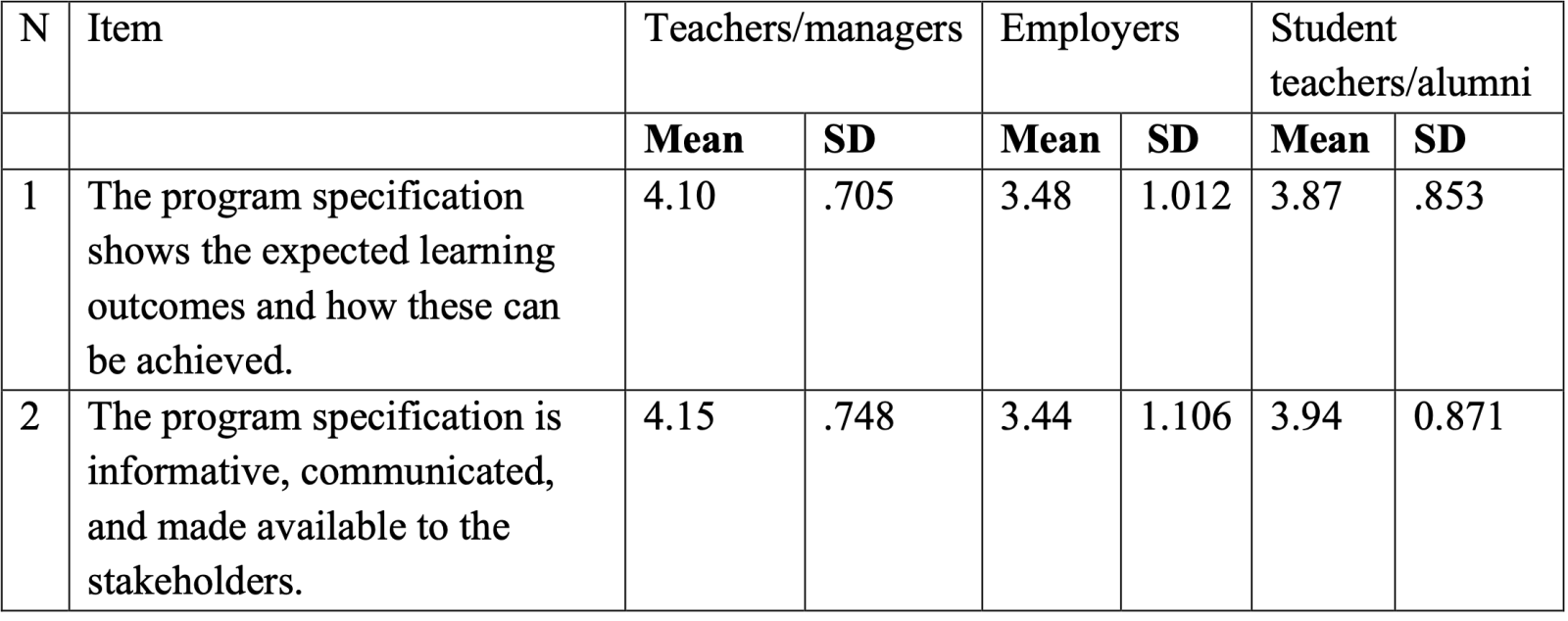

Program Specification

Information regarding the program’s expected learning outcomes, curriculum, teaching strategies, assessment methods, and other supporting activities should be sufficient and made available and accessible to students, teachers, and potential employers for decision-making purposes. In terms of this criterion, teachers/managers rated their program higher than employers and student teachers, at 4.10 compared with 3.44 and 3.87, respectively. Over half of the employers (56%) and three-quarters of the student teachers/alumni (77%) agreed that they were informed about the program.

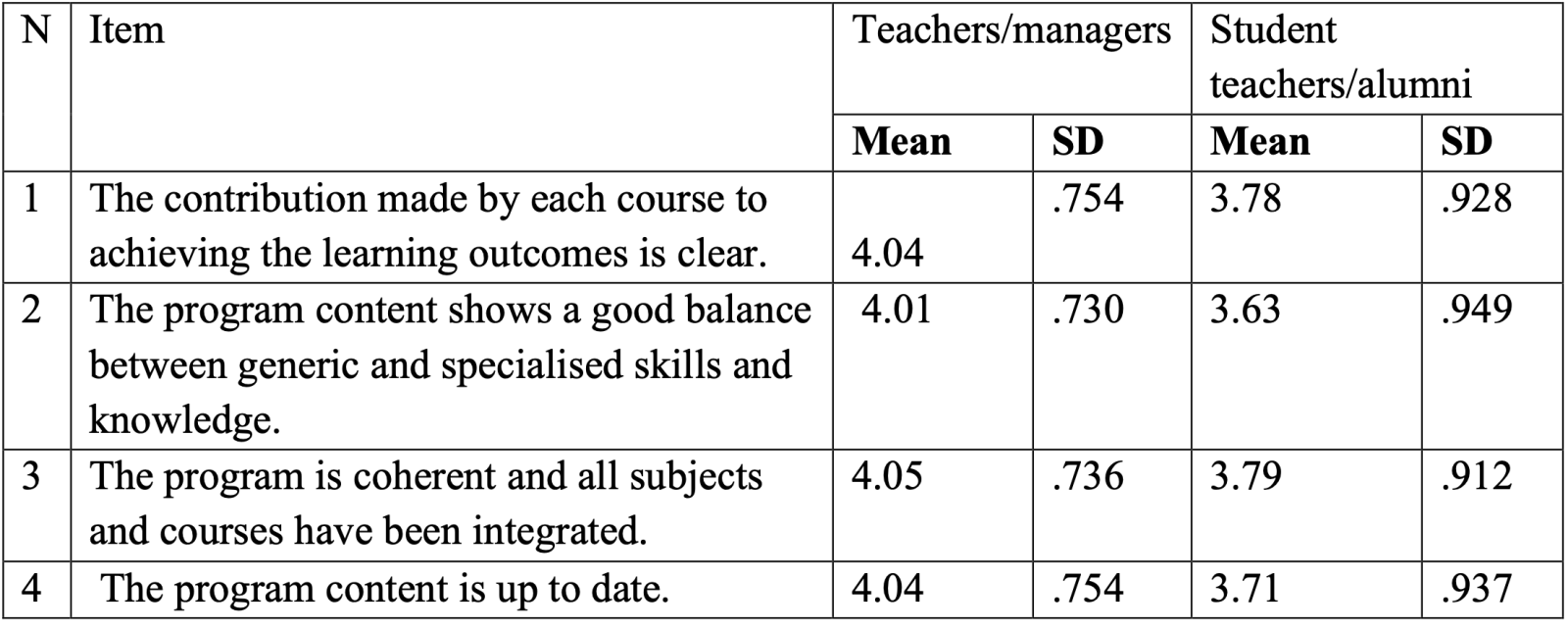

Program Content and Structure

AUN-QA requires that the curriculum be designed in such a way that courses contribute to the development of the program’s expected learning outcomes. There should be a balance among different knowledge components and course content should be regularly updated to incorporate latest developments in the discipline and professional practices. Regarding these criteria, student teachers/alumni rated the program lower than teachers/managers, with 60% of the student teachers/alumni agreeing with the statements regarding curriculum content and structure.

The Teaching and Learning Approach

Teaching and learning activities in the program should be varied and appropriate to achieve expected learning outcomes. 66% of student teachers/alumni expressed their agreement and 25% had no opinions regarding the criteria on instructional strategies and methods.

.png)

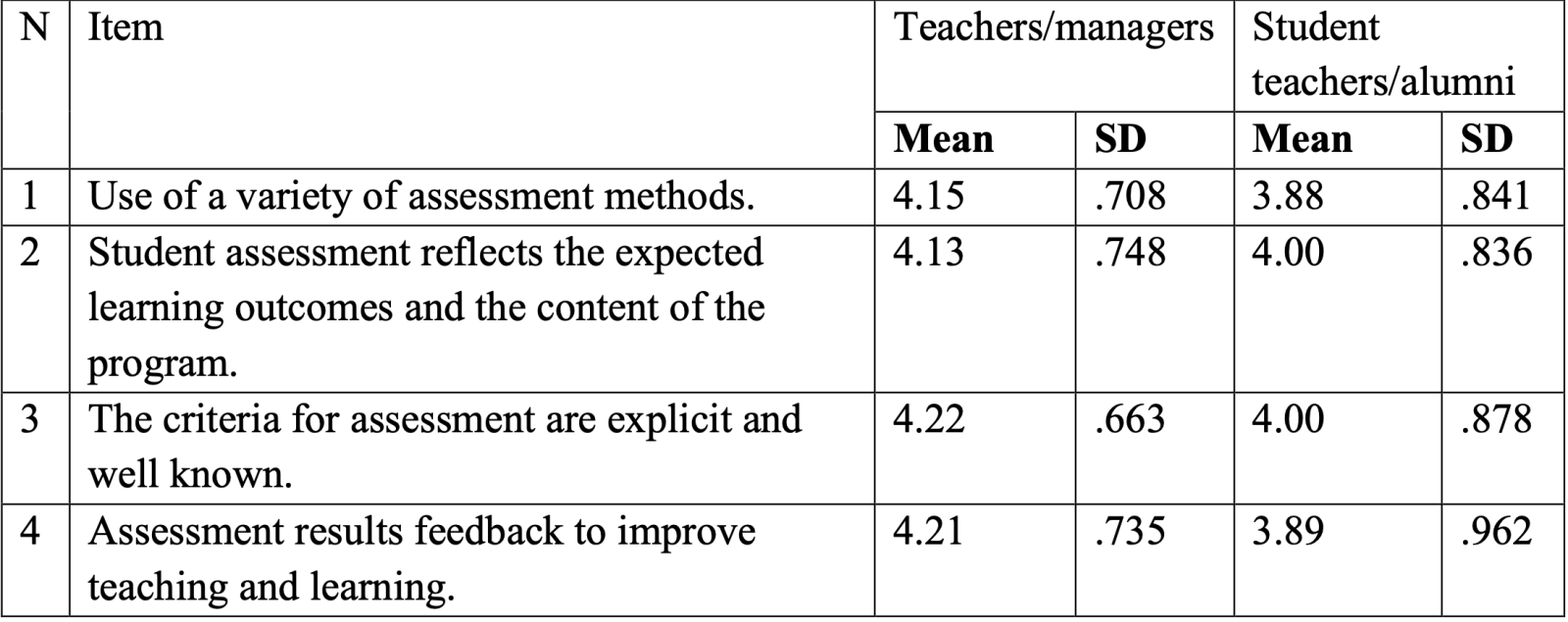

Student Assessment

In order to assess learning outcomes properly, there should be a variety of assessment methods used that reflect the learning outcomes and program content. Students should be informed about the purposes, methods, and criteria for assessment in order to orient their learning. Feedback from assessment should be used to improve teaching and learning. In this criterion, both teachers/managers and student teachers/alumni rated the program higher than others. The average rating for teachers/managers was 4.18 compared with 3.94 for student teachers/alumni. 75% of student teachers/alumni agreed with the statements and 20% had no opinion.

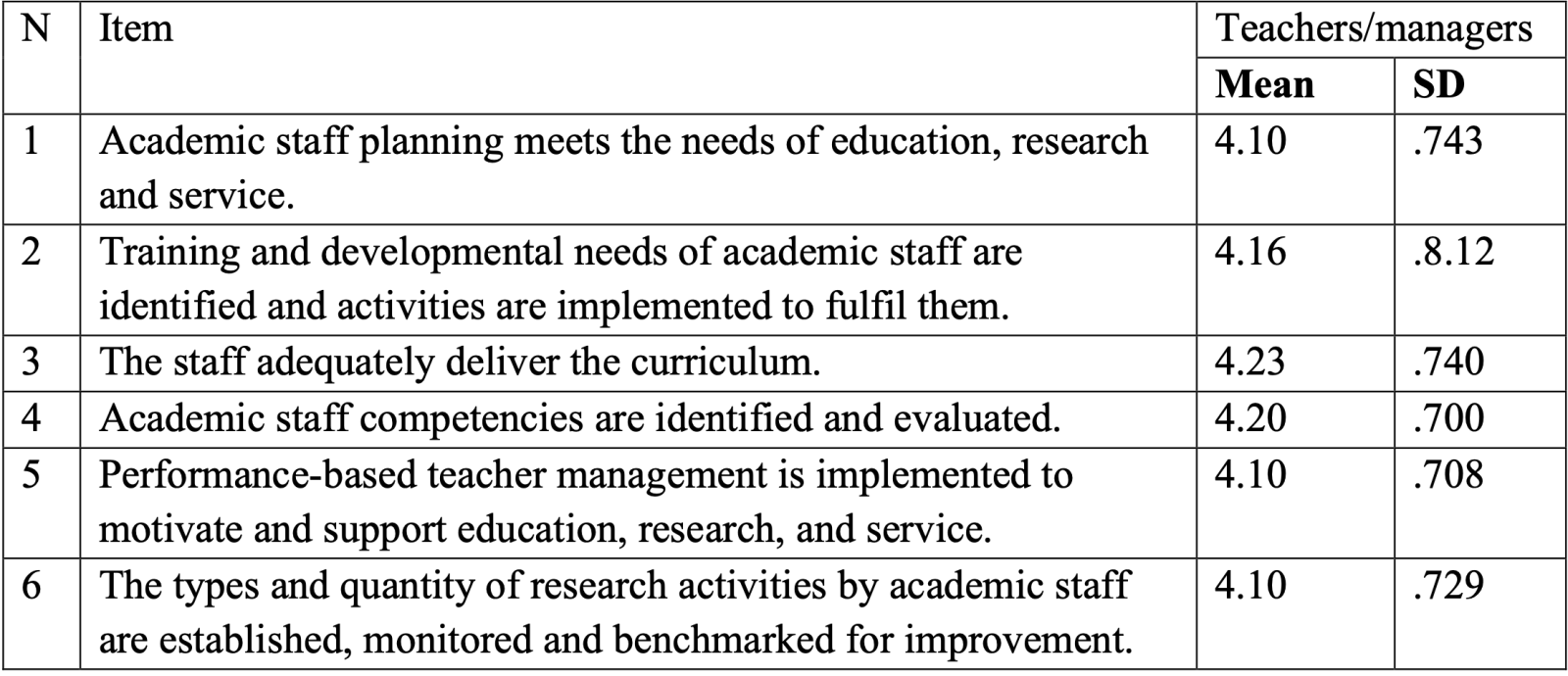

Academic Staff Quality

To ensure the quality of academic staff, the institution should organise professional development programs to meet the needs for teaching and research. Programs are also required to have sufficient and competent teachers. The management of teachers must be performance-based. There should also be requirements regarding research activities for academic staff. In this category, teachers/managers rated their program quite high (4.15 on average), with over 80% of them expressing agreement with the statements.

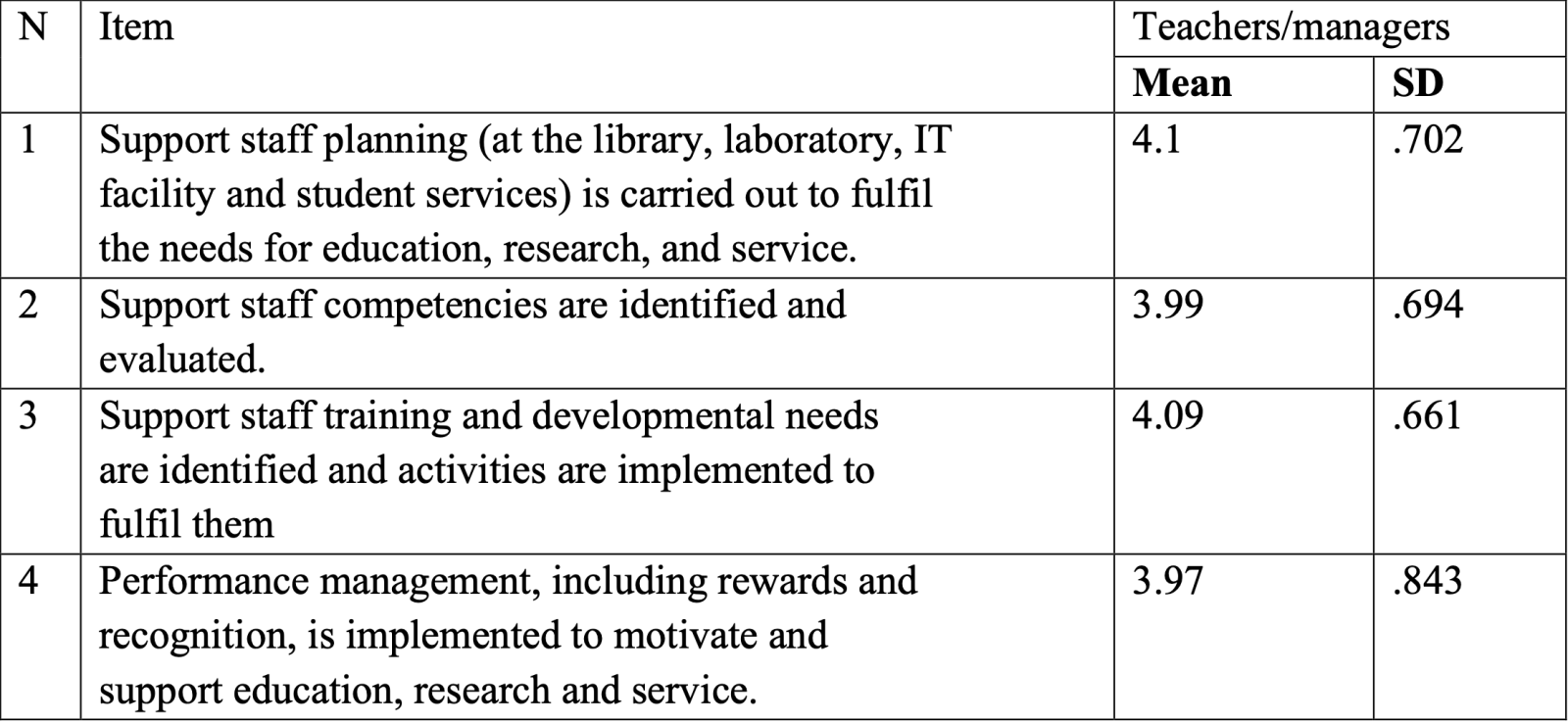

Support Staff Quality

Quality education and research depend on the availability, sufficiency and competencies of support staff. The study findings show that initial teacher education programs have policies and actions to ensure that support staff is adequate for teaching, learning and research and to manage and develop the staff professionally. Teachers and managers had relatively strong

evaluations of their support staff, with an average of 4.05. Around 70% of the teachers/managers agreed with QA practices in this area.

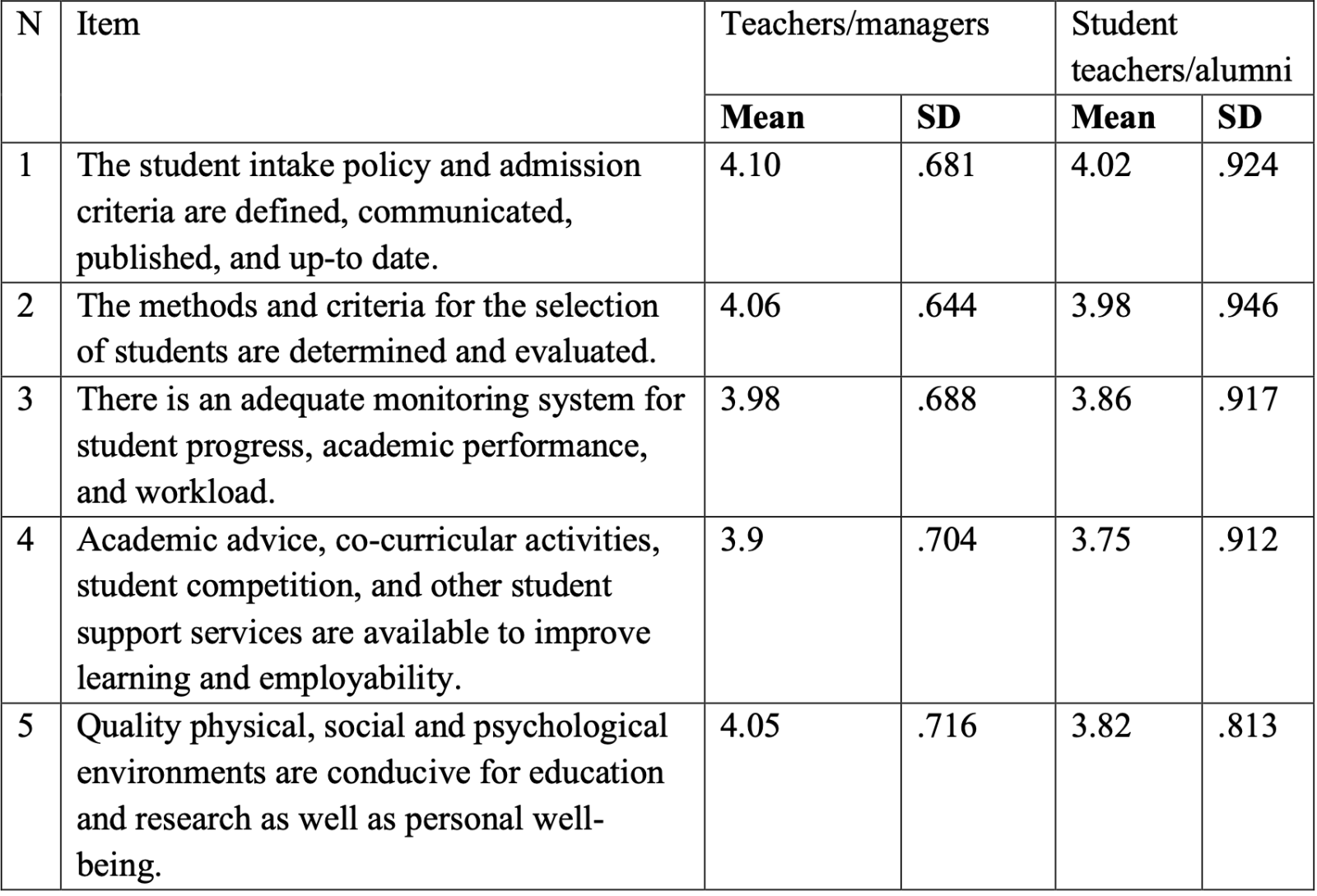

Student Quality and Support

In order to produce quality students, it is required that the program have clearly defined policies and admission criteria that are subjected to regular evaluation. In this criterion, the majority of teachers/managers and student teachers/alumni expressed positive evaluation, accounting for almost more than three-quarters of the participants. Learning and other student support services during the program are also requisite to enable strong performance and achievement among student teachers. In this area, both teachers/managers and student teachers/alumni expressed lower ratings, 3.9 and 3.75, respectively. More than two-thirds of student teachers/alumni expressed their satisfaction with admission criteria and supporting activities.

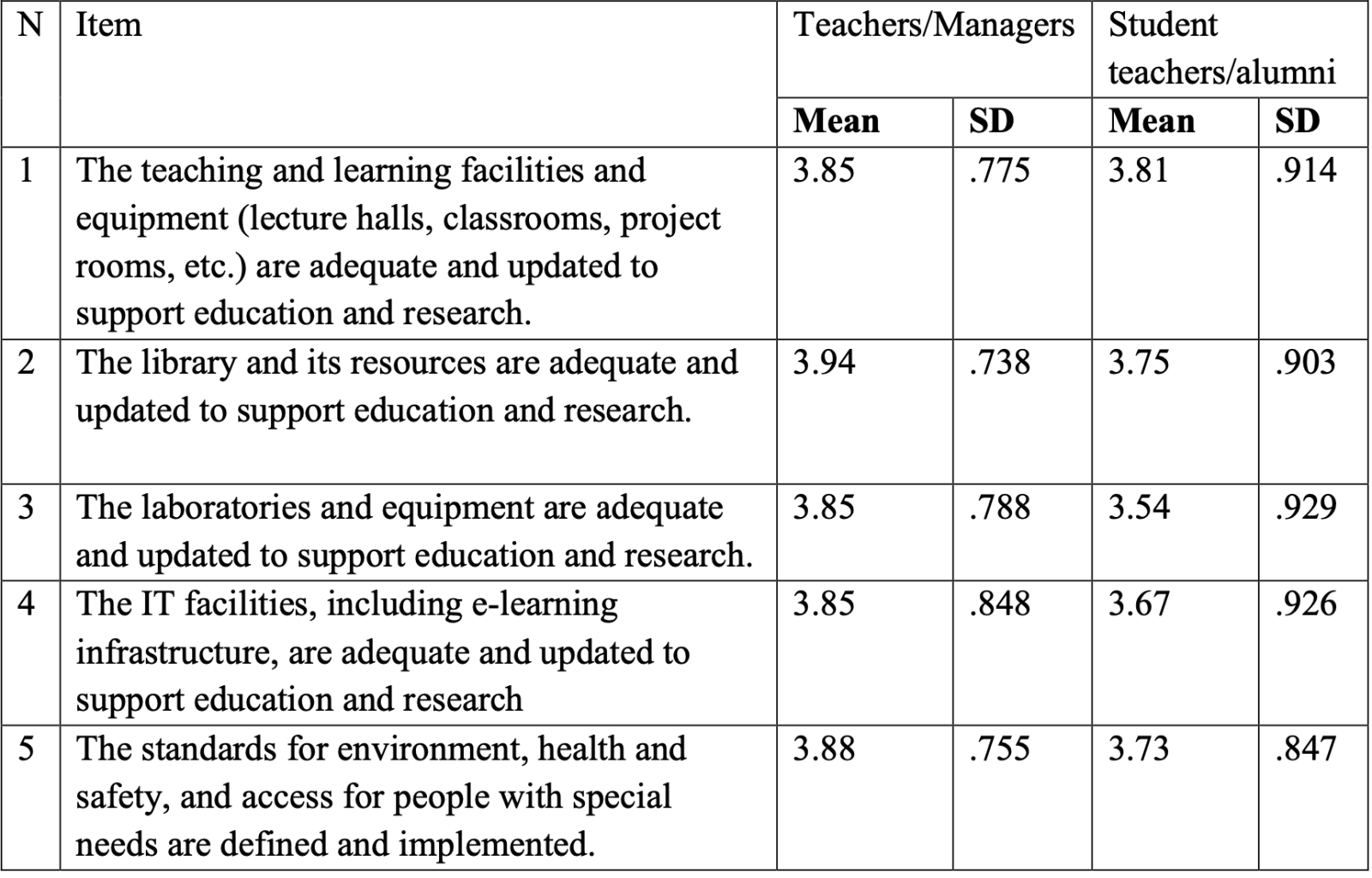

Facilities and Infrastructure

It is required that teaching and learning facilities and equipment, libraries, resources, laboratories are adequate to support education and research. In these criteria, only about 70% of teachers/managers expressed positive evaluation. Student teachers/alumni rated the program a little lower in these criteria, with around 66% either agreeing or strongly agreeing with the statements.

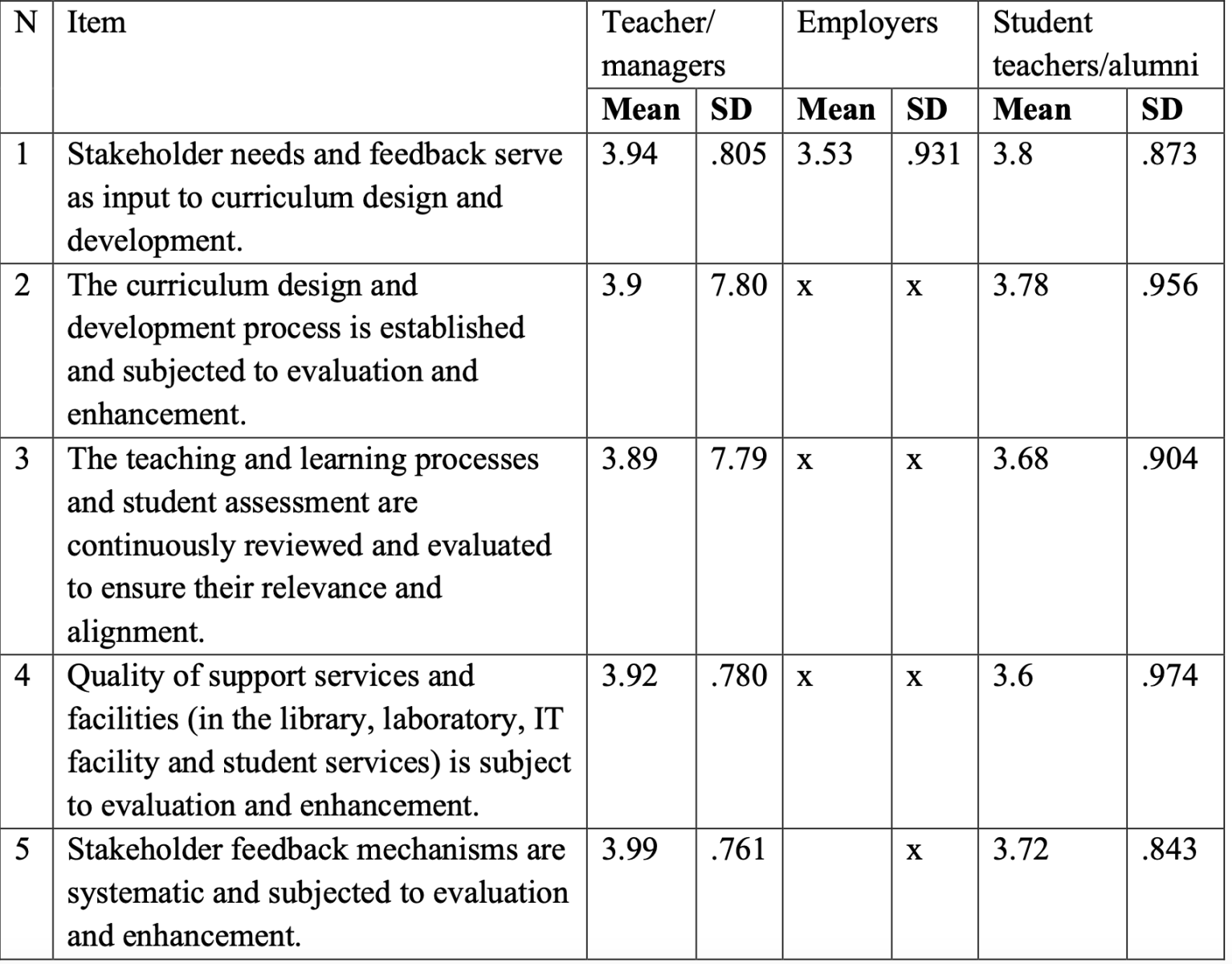

Quality Enhancement

Another criterion for assuring program quality is constant improvement. It is required that the program have mechanisms in place to ensure that it is regularly evaluated and improved. Stakeholders, including society, employers, students, academic staff and managers, should be consulted to provide input for program development. Curriculum, teaching, learning, and assessment are also subjected to regular revision and improvement. Both employers and student teachers/alumni rate this category lower than teachers/managers. Approximately 64% of the employers said that they had been asked to contribute their opinion in developing the curriculum. A similar proportion of student teachers/alumni surveyed gave the same opinion. In comparison, 75% of teachers/managers expressed their satisfaction with the quality enhancement practices in their program.

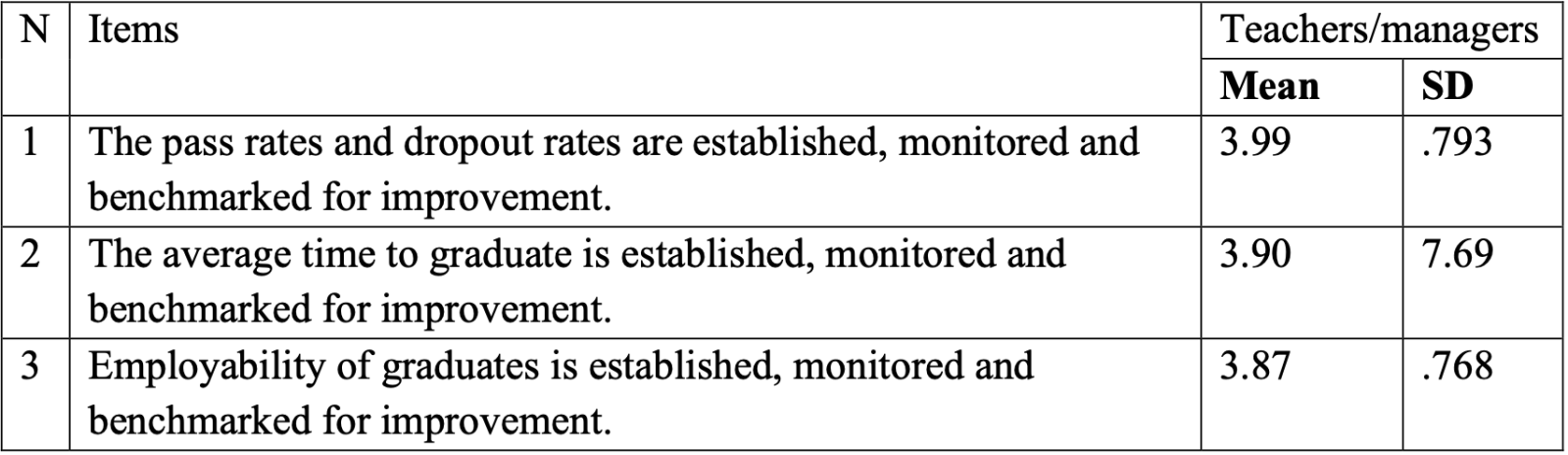

Output

A quality program needs to have mechanisms in place to monitor and improve output, including pass rates, dropout rates, average graduation time, and employability of graduates. Around 75% of the teachers/managers surveyed gave positive evaluation for this criterion.

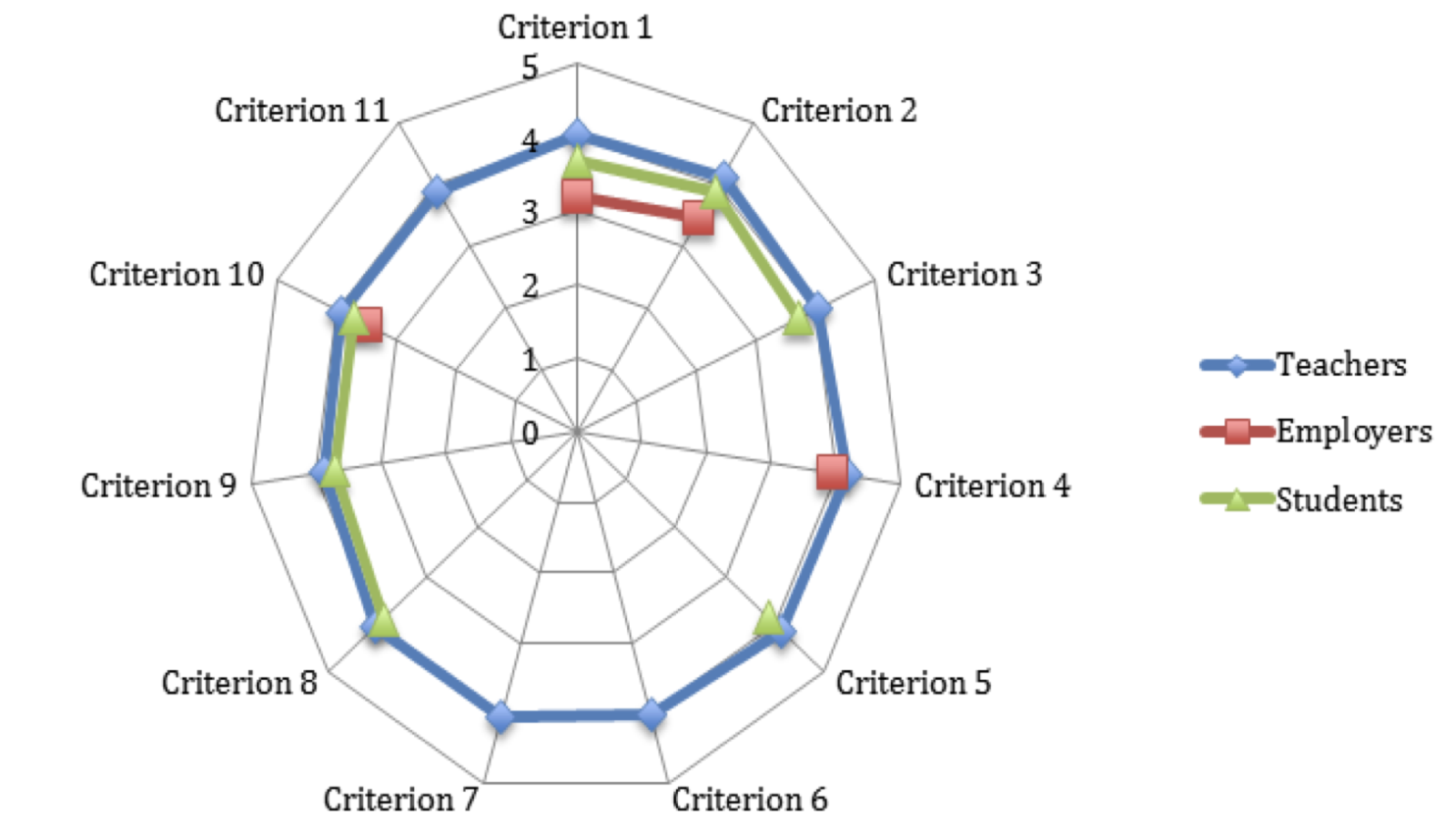

Overall teachers/managers’ ratings of the program QA were higher than those of the student teachers/alumni and employers in most criteria. Particularly, in criteria 1, 2, employers rated the program significantly lower, at 3.3 to 3.5, respectively. These criteria are concerned with the extent to which the program’s expected learning outcomes reflect stakeholder requirements and the availability and accessibility of the program information. The balance between different knowledge components within the curriculum was another area of concern where student teachers/alumni had lower ratings.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study shows that the teacher education programs studied have undertaken internal quality assurance policies and practices to ensure that the program objectives are met and quality is constantly improved. The programs’ expected learning outcomes, to a certain extent, are formulated in a way that satisfies various stakeholders’ needs. However, the study suggests that teacher education programs’ expected learning outcomes need to better reflect the requirements for teaching competencies at schools. Chong and Ho (2009) observed that the quality assurance of the initial preparation of teacher programs in Singapore started with establishing the values, skills and knowledge frameworks that reflected desired attributes of starting teachers. Similarly, AITSL (2011) maintains that defining professional standards for teachers, i.e. professional knowledge, practice, and engagement, is an effective way to improve teacher quality.

The programs had arranged the curriculum content and structure, instructional strategies, and learning assessment to achieve the expected learning outcomes. The survey responses, however, indicated a noticeable lack of balance between knowledge and skill components within the curriculum content. The study findings indicate that programs focus more on the knowledge components, probably expecting that prospective teachers will translate them into classroom practices. It is therefore recommended that future teachers should be equipped

with adequate pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge, and teaching skills in order to function properly in schools (Bransford et al., 2005; NCATE, 2008). It is also recommended that academic and professional learning should be equally focused on during the program. In terms of instructional strategies and assessment practices, quality assurance ensures teaching, learning, and assessment results for the achievement of the desired learning outcomes. Tran, Nguyen, and Nguyen (2011), however, caution that improving teaching or lecturing techniques of Vietnamese teachers does not necessarily lead to quality student learning. They therefore suggest that conceptual changes are required to enable student- centred approaches to teaching and learning that achieve the expected learning outcomes.

Regarding student and supporting activities, there are measures that the initial teacher education programs can undertake to strengthen the quality of student teachers. These include, among others, establishing prerequisites for entry into teacher education programs, and raising the level of prior entrant academic achievement. It was found that in most countries, future teachers are recruited from above-average achievers, and in some countries, from the top 20% of the age cohort (Eurydice, 2006).

The quality enhancement of the educational program (i.e. of curriculum, teaching, learning, assessment, students, supporting services, facilities, and infrastructure) was an important QA practice undertaken by the teacher education programs. Ongoing quality development, rather than the mere technical concern of conforming to external standards for accountability, should be the primary goal of quality assurance (Smith & MacGregor, 2009). This quality improvement is enabled through developing internal quality culture that involves the autonomous participation of faculty members (Ezer & Horin, 2013). Partnership and cooperation between teacher education programs and schools in developing the curriculum and providing practical knowledge and teaching experiences are effective measures to better achieve the expected outcomes pertaining to professional competence (Treagust, Won, Peterson, & Wynne, 2015).

While quality assurance is still a novel concept in Vietnam’s higher education, this study shows that teacher education institutions have embraced quality assurance in their policies and practices. The results also suggest that QA policies and practices among teacher education programs should be improved for greater achievement of expected learning outcomes and satisfaction of stakeholder needs.

REFERENCES

AITSL. (2011). National professional standards for teachers. Melbourne: Education Services Australia.

ASEAN University Network (AUN) (2015). Guide to AUN-QA Assessment at Programme Level. Bangkok, Thai Lan: AUN.

Biggs, J. (2001). The reflective institution: Assuring and enhancing the quality of teaching and learning. Higher Education, 41, 221-238. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1004181331049

Bransford, J., Darling-Hammond, L., & LePage, P. (2005). Introduction. In L. Darling_Hammond & J. Brandsford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do (pp. 1-39). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Brennan, J. (2018). Success factors of quality management in higher education: intended and unintended impacts. European Journal of Higher Education. doi:10.1080/21568235.2018.1474776

Cheng, Y., & Tam, W. (1997). Multi-models of quality in education. Quality Assurance in Education, 5(1), 22-31. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684889710156558

Cheng, Y. C. (2003). Quality assurance in education: Internal, interface and future. Quality Assurance in Education, 11(4), 202. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880310501386

Chong, S., & Ho, P. (2009). Quality teaching and learning: A quality assurance framework for initial teacher preparation programme. International Journal of Management in Education, 3(3/4), 302-314. doi:10.1504/IJMIE.2009.027352

Cochran-Smith, M. (2001). The outcomes question in teacher education. Teaching and Teacher Education, 1, 527-546.

DEEWR. (2008). Quality assurance arrangements in higher education in the broader Asia- Pacific Region. Melbourne: Asia-Pacific Network Inc.

Eurydice. (2006). Quality assurance in teacher education in Europe. In E. Commission (Ed.). Brussels: Eurydice.

Ezer, H., & Horin, A. (2013). Quality enhancement: a case of internal evaluation at a teacher college. Quality Assurance in Education, 21(3), 247-259.

Harford, J. (2010). Teacher education policy in Ireland and the challenges of the twenty-first century. European Journal of Teacher education, 33(4), 349-360. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2010.509425 International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 10, 2020 243

Harvey, L., & Green, D. (1993). Defining quality. . Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 18(1), 9-34. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0260293930180102

Harvey, L., & Knight, P. T. (1996). Transforming higher education. London, UK: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

Haycock, K., & Huang, S. (2001). Are today's high school graduates ready? Thinking K-16, 5(1), 3-17.

Hudson, B., Zgaga, P., & Astrand, B. (2010). Advancing quality cultures for teacher education in Europe: Tensions and Opportunities, : University of Umea.

Ingvarson, L., & Rowley, G. (2017). Quality assurance in teacher education and outcomes: A case study of 17 countries. Educational Researcher, 46(4), 177-193. doi:10.3102/0013189X17711900s

Lagrosen, S., Seyyed-Hashemi, R., & Leitner, M. (2004). Examination of the dimensions of quality in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 12(2), 61-69. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/09684880410536431

Learning, C. o. (1997). Quality assurance toolkit: Distance higher education institutions and programmes.

Martin, M., & Stella, A. (2007). External quality assurance in higher education: Making choices. Paris, France: United Nations.

NCATE. (2008). Professional standards for the accreditation of teacher preparation institutions. Washington DC.

Nguyen, H. C. (2017). Impact of international accreditation on the emerging quality assurance system: The Vietnamese experience. Change Management: An International

Journal, 17(3), 1-9. DOI: https://doi.org/10.18848/2327-798X/CGP/v17i03/1-9.

Nguyen, H. C. & Ta, T. T. H. (2018). Exploring impact of accreditation on higher education in developing countries: A Vietnamese view. Tertiary Education and Management, 24(2), 154-167. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/13583883.2017.1406001

Nguyen, H. C., Ta, T. T. H., & Nguyen, T. T. H. (2017). Achievements and lessons learned from Vietnam's higher education quality assurance system after a decade of establishment. International Journal of Higher Education, 6(2), 153-161. doi:https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v6n2p153

Nguyen, K. D., Oliver, D. E., & Priddy, L. E. (2009). Criteria for accreditation in Vietnam’s higher education: focus on input or outcomes. Quality in Higher Education,, 15(2), 123-134.

International Journal of Innovation, Creativity and Change. www.ijicc.net Volume 12, Issue 10, 2020 244

Nhan, T. T., & Nguyen, H. C. (2018). Quality challenges in transnational higher education under profit-driven motives: The Vietnamese experience. Issues in Educational Research, 28(1), 138-152. http://www.iier.org.au/iier28/nhan.pdf

Nicholson, K. (2011). Quality assurance in higher education: A review of literature. Council of Ontario Universities Degree Level Expectations Project. https://works.bepress.com/karen_nicholson/19/

Sacilotto-Vasylenko, M. (2013). Bologna process and initial teacher education reform in France. International Perspectives on Education and Society, 19, 3-24.

Sanayl, B. C. (2013). Quality assurance of teacher education in Africa: Addis Ababa.

Schindler, L., Puls-Elvidge, S., Welzant, H., & Crawfod, L. (2015). Definition of quality in higher education: A synthesis of the literature. Higher Learning Research Communication, 5(3). doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.18870/hlrc.v5i3.244

Smith, B. L., & MacGregor, J. (2009). Learning communities and the quest for quality. Quality Assurance in Education, 17(2), 118-139.

Tam, M. (2010). Measuring quality and performance in higher education. Quality in Higher Education, 7(1), 47-54. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13538320120045076

Tam, M. (2014). Outcomes-based approach to quality assesment and curriculum improvement in higher education. Quality Assurance in Education, 22(2), 158-168. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/QAE-09- 2011-0059

Tran, N. D., Nguyen, T. T., & Nguyen, M. T. N. (2011). The Standard of quality for HEIS in Vietnam: a step in the right direction? Quality Assurance in Education, 19(2), 130-140.

Treagust, D. F., Won, M., Peterson, J., & Wynne, G. (2015). Science teacher education in Australia: Initiatives and challenges to improve the quality of teaching. Science teacher education in Australia, 26, 81-98. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-014-9410-3

UNESCO. (1998). World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century: Vision and action. Retrieved from http://www.unesco.org/education/educprog/wche/declaration_eng.htm

- Professional skills development for University lecturers: A case study in the Mekong Delta region of VietnamNghiên cứu10/06/2025

- Management of primary teacher training programs using the CDIO approach: Theoretical frameworks and practical implementationsNghiên cứu03/06/2025

- Nghiên cứu mối liên quan giữa tật cận thị và một số yếu tố khác với tình trạng lo âu của sinh viên 2 năm đầu đại họcNghiên cứu22/05/2025

- Mối liên quan giữa tình trạng lo âu với tật cận thị và một số yếu tố khác của sinh viên năm cuối đại họcNghiên cứu13/05/2025

- Đổi mới quản lý cơ sở giáo dục đại học trong bối cảnh tự chủ đại họcNghiên cứu01/05/2025

- Xây dựng và sử dụng khung năng lực trong phát triển đội ngũ giáo viên làm công tác tư vấn học đường ở trường tiểu họcNghiên cứu07/04/2025

- Tổng quan các nghiên cứu phát triển năng lực số cho sinh viên đại học ngành giáo dục tiểu họcNghiên cứu04/04/2025

- Bản đồ cơ thể đầu tiên về ảo giácNghiên cứu01/04/2025

- Điểm chuẩn ngành Sư phạm Tin họcKhoa Tin học23/08/2025

- Khoa Ngữ văn công bố mục tiêu và chuẩn đầu ra chương trình đào tạo trình độ thạc sĩ Ngôn ngữ Việt NamĐào tạo21/08/2025

- Nghiên cứu mới cho rằng cần có một định nghĩa mới về chứng khó đọc (dyslexia)Tin tức20/08/2025

- Học viên cao học K30 bảo vệ luận văn/đồ án Thạc sĩ ngành Quản lý giáo dục với loạt đề tài sát thực tiễnĐào tạo17/08/2025

- Thuốc điều trị ADHD giúp giảm nguy cơ tự tử, lạm dụng chất gây nghiện và hành vi phạm tộiTin tức15/08/2025

- Thông báo KQ xét cộng điểm thưởng cho thí sinh có thành tích vượt trội xét tuyển vào đại học chính quy trường Đại học Vinh năm 2025Tin tức15/08/2025

- Các chatbot trí tuệ nhân tạo (AI) có thể bị khai thác để trích xuất thêm nhiều thông tin cá nhân.Tin tức14/08/2025

- Mèo mắc chứng sa sút trí tuệ có những đặc điểm điển hình tương đồng với bệnh AlzheimerTin tức13/08/2025